Yan Khouvry was out fishing till 7 a.m. on Tuesday morning. He had set out late morning on Monday and plied the waters near Koh Dach all day and night.

He returned with just two fish. Later on Tuesday morning, around 10 a.m., he was preparing to do it all over again.

“It’s very difficult. Every day, it’s difficult,” Khouvry says. “It’s nearly October — look at the water.”

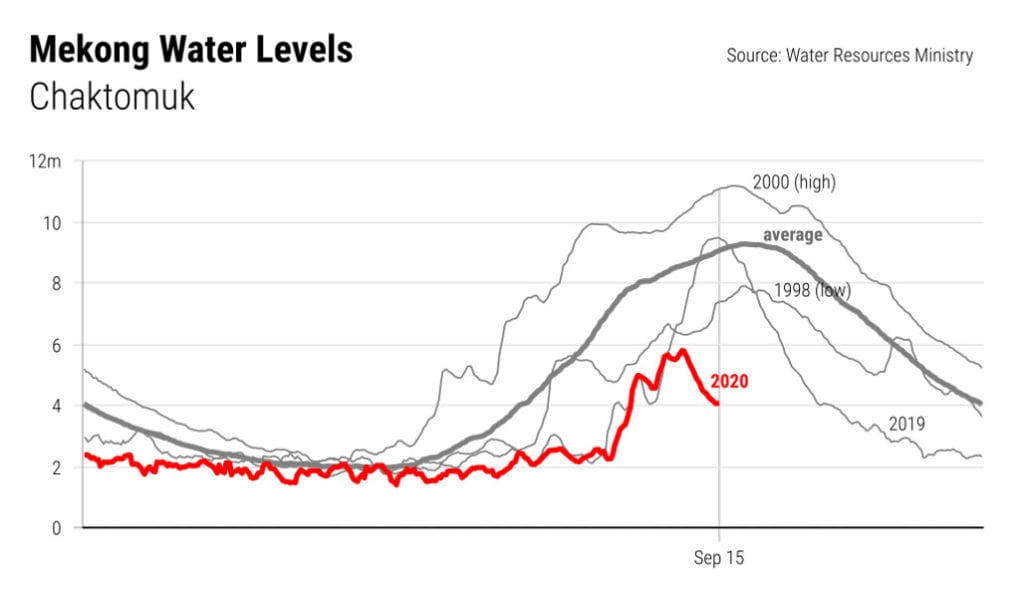

This week, the Mekong River was measured at 4 meters deep at Phnom Penh’s Chaktomuk. The recorded average for this time of year is 9 meters. In 1998, when the Water Ministry recorded the previous low peak, it was 7.4 meters.

“The lower the water, the less fish we have,” Khouvry says. “We eat in the mornings, but not in the evenings.”

Over decades, Cham Muslim fishing families living on Phnom Penh’s Chroy Changva peninsula have been repeatedly kicked off their previous settlements and pushed down to its southernmost tip, where about 1,500 people now live, according to the village chief. They moor their boats under the shadow of the luxury Sokha Hotel, where the Mekong and Tonle Sap meet, on a narrow strip between the peninsula’s ferry terminal and the next road to the northeast.

This year, amid record-low waters, the families fear they will need to finally leave Phnom Penh behind, with local authorities threatening their eviction to make way for a private development, and a search for new shores nearby coming up empty.

Village chief Y Yo, 60, arrived at the peninsula’s southernmost point in 2010, following years of repeated harassment. He has lived on Chroy Changva since the ouster of the Khmer Rouge in 1979, but this may be his last stop.

The threat of a final eviction and the worst fishing in memory have come at once, he says.

“Every September the water floods this area,” Yo says, sitting under a makeshift roof. “But this year there’s no water.”

A villager points to about shoulder-height on a post to show how high the water typically gets around this time of the year. But this year, the shore is more than 50 meters away.

Everyone in the village is a fisher, so everyone is affected, Yo says.

Om Savath, executive director of the Fisheries Action Coalition Team, shares the concern. September should be the peak for water levels in the Mekong region’s rivers, but they have hardly risen this year, he says. Some 60 million people depend on the rivers for their livelihoods, he says.

“The government will say it’s the effects of climate change,” Savath says. But he disagrees. Hydropower dams upstream — especially in Laos and China — have cut off the water flow on the Mekong, he says, a view backed by a recent study.

It has affected the Tonle Sap as well, which normally floods into surrounding forests every year, creating breeding grounds for fish. Savath says the lake is currently about 4 meters deep, less than half the depth of other years.

But in the Chroy Changva community, the lack of fish is not the only fear. In April, city and district officials came to evict the families. Yo, the village chief, says he begged to be allowed to stay a little longer, but everyone knows it is a matter of time.

Yo’s wife, Sos Nop, 49, says the looming eviction never leaves their minds. “We sleep every day worrying about when we’re going to be kicked out, and where we’re going to live.”

Yo adds: “We eat, we think about it. We sleep, we think about it. This land belongs to powerful people, so we can’t stop them.”

The community searched nearby shores for a new home, but every stretch seemed to already be taken by the monied, he says.

“Go left, it belongs to someone. Go right, it belongs to someone. So where do we go? Every part of the shore belongs to someone. This water belongs to them too,” he says. “They kick the poor out, and the rich’s buildings grow. They don’t allow the poor to be close to the rich.”

Yo says the community doesn’t want much — just a place to moor their boats, a mosque and access to education.

“Forget about my generation,” he says. “We just want a place for our children.”

Chroy Changva commune chief Kang Phana says authorities have already informed the villagers about the upcoming evictions two or three times.

“The district has issued an announcement under the instruction of the Phnom Penh municipal governor,” Phana says. “[Booyoung Group] bought land there long ago for development. People asked to stay there temporarily on the unused area.”

People who answered listed Cambodian phone numbers for Booyoung, a South Korean conglomerate, hung up on reporters. District governor Klang Huot declined to comment.

On Chroy Changva, Nas Ly, 54, searched the shore in distress on Tuesday. One of his two boats was stolen overnight, he says.

When asked if he would ask the police for help, Ly laughs. “They’ll say, ‘We will search for you.’ And when have they actually searched?”

Khouvry, the fisherman preparing for the day’s voyage, says he is turned away everywhere he goes. When he wants to moor his boat near the capital’s Riverside area to take his fish to market, he is told to leave. If he wants to drop off his children at school by boat, he is denied.

He says he feels humiliated. “But we have to endure it.”

“It’s our life. We are poor,” Khouvry says. “When you don’t have power, they hurt you.”

He knows he, his wife and three children, aged 3, 5 and 8, will soon need to leave again, after six years on the southernmost end of Chroy Changva. He wants a permanent home, but he has little hope.

“How could you help me?” Khouvry retorts doubtfully, when asked about notifying reporters once the evictions finally happen. “They turn a blind eye. They don’t care what the media covers.”

“We want to have a place to settle, like other people,” he says. “But we can’t move forward. We’re stuck on the boat.”

Note: This report was produced with support from the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation under the financial support of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development.