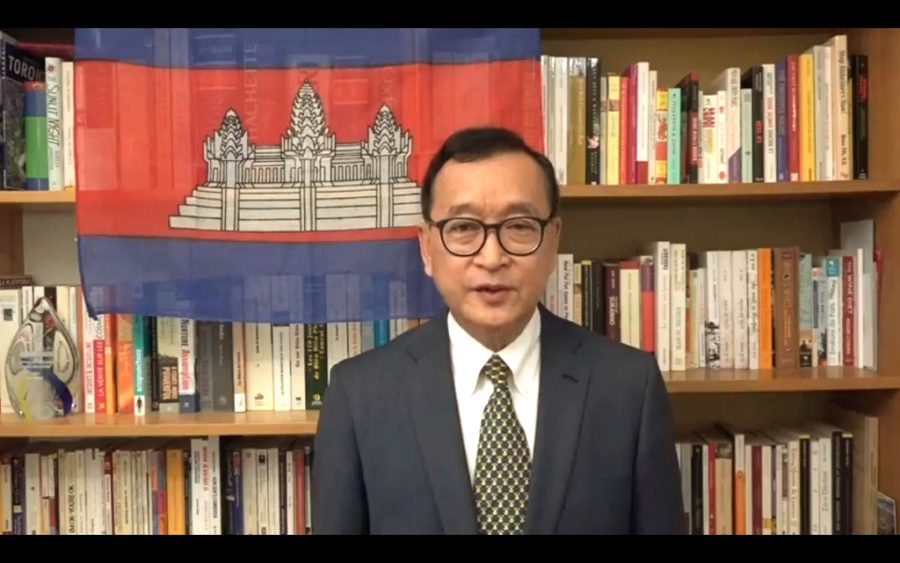

As opposition leader Sam Rainsy vowed to put his freedom and life on the line in his attempt to return to Cambodia on November 9, the ruling party said on Tuesday that the day would mark his “final day.”

Sok Eysan, spokesman of the ruling Cambodian People’s Party, said the rhetoric of Rainsy, acting president of the banned Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP), was mere rabble-rousing, a desperate attempt to incite Cambodians and use them “as a springboard to demand power.”

It was also a way to hype himself up so he would not, once again, back down from a promise to try to return from exile, Eysan said.

However, the spokesman added that the day would also be the end of Rainsy, without specifying if that meant the end of the long-time opposition leader’s political career, freedom or life.

“We’ve already known that he is coming close to his final day. November 9 is the final day of the outlawed rebel leader,” Eysan said.

Rainsy has been living abroad since late 2015 to evade court actions against him, the most recent of which has seen him charged with “attack,” or the commission of acts of violence liable to endanger Cambodian institutions.

On August 16, he pledged to attempt a return to the country on November 9. He has called Cambodian workers living in Thailand — whose numbers are estimated at 1.5 million — to join him across the border.

The government has called Rainsy’s planned return a coup attempt, and any supporters guilty of the crime of plotting. About 40 former CNRP members have been arrested since Rainsy’s announcement, and dozens more charged.

The CNRP, founded as a merger between the Sam Rainsy Party and co-founder Kem Sokha’s Human Rights party in 2012, was dissolved by the Supreme Court in November 2017, eight months ahead of a national election. Its leader Kem Sokha was arrested in September 2017. He remains under de-facto house arrest.

On Tuesday, Rainsy said in a widely disseminated email that he would “restore” democracy through “People Power” on November 9.

“The opposition party I founded with Kem Sokha succeeded in collecting practically half of the popular vote despite being continuously harassed. It has been arbitrarily dissolved and therefore prevented from participating in any future election,” he said.

“I therefore have no option left but to return to Cambodia in a non-violent way to restore democracy by creating an example of People Power similar to in the Philippines in 1986.”

In 1986, sustained demonstrations against long-time president Ferdinand Marcos — who ruled by martial law earlier in the decade — led to an overthrow of the government. Events that year included a failed coup attempt led by the then-defense minister. Three years earlier, opposition leader Benigno Aquino Jr. was assassinated at Manila International Airport upon his return home from three years in self-imposed exile.

“I am prepared to sacrifice my freedom — and even my life — to give democracy a chance, to help ensure freedom for my unfortunate people,” Rainsy said.

Political analyst Meas Nee, however, said neither side had sufficiently considered what was best for Cambodia’s population.

Both sides of the dispute seemed trapped in thinking of only their self-interest rather than the benefit of the country, he said, pointing to partisanship as the root cause of the mounting tensions.

“If we do not respond to the root cause of the issue, and we continue to do what we always have, the issue will not leave us,” Nee said.

(Translated and edited from the original article on VOD Khmer)