Kirsten Han is a Singaporean freelance journalist and activist who was involved in advocating against the passage of the Foreign Interference (Countermeasures) Act in Singapore last year. She currently runs the newsletter, We, The Citizens, covering Singapore from a rights-based perspective, and tweets @kixes.

Kirsten Han is a Singaporean freelance journalist and activist who was involved in advocating against the passage of the Foreign Interference (Countermeasures) Act in Singapore last year. She currently runs the newsletter, We, The Citizens, covering Singapore from a rights-based perspective, and tweets @kixes.

The only thing that makes me feel worse about Singapore’s anti-foreign interference law is seeing it spread beyond our borders.

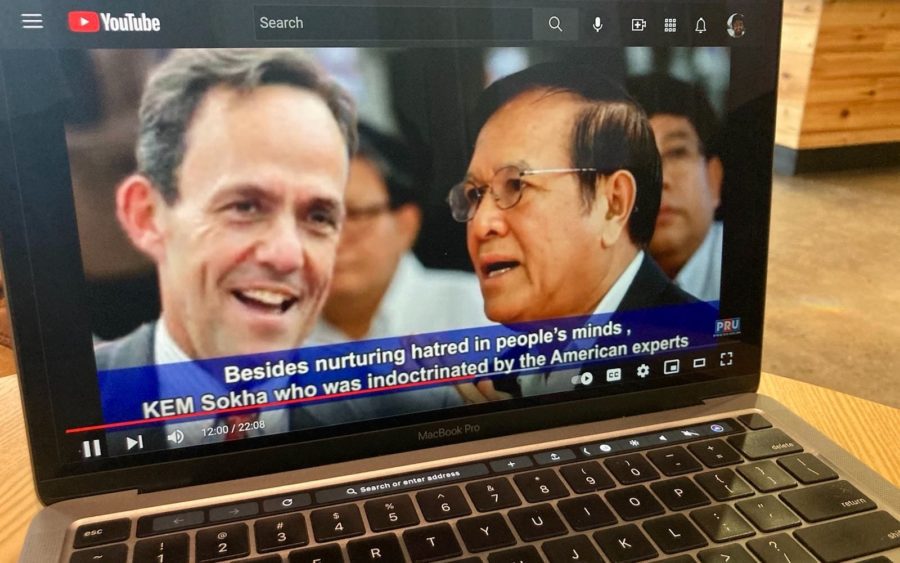

Singapore’s Parliament passed the Foreign Interference (Countermeasures) Act, or FICA, last October. It has not yet come into force here, but it’s depressing to see that its influence has already spread to Cambodia. If the Cambodian government adopts a similar law, or directly imports FICA into its statues, the target on the backs of opposition politicians, NGOs, civil society activists and journalists will likely grow bigger. And, just to rub salt into the wound, the law won’t even adequately deal with genuine concerns of foreign interference.

As a piece of legislation, FICA was written to grant the government and their appointed authorities maximum discretions. Under its extremely broad definitions, a “foreign principal” can be anyone who isn’t a citizen or locally-registered entity. “Engaging in conduct on behalf of a foreign principal” can be as simple as having an “arrangement” with the foreigner, working in collaboration with them, or accepting funding from them. Meanwhile, the definition of what constitutes activity “directed towards a political end” includes attempts to seek changes to law or to influence public opinion, which could easily cover any work done by civil society or the media. Alarmingly, the law also cuts the courts out of the equation, directing appeals against FICA orders to a Reviewing Tribunal (essentially appointed by the government) or to the Minister for Home Affairs.

Such a law puts a huge amount of power in the government’s hands, with no meaningful check or oversight. It leaves anyone or any organisation doing work that challenges the government’s power or interests at risk of becoming branded a local proxy of some foreign meddler, which could lead to censorship, harassment, or even criminal penalties. The part of the law that allows the government to designate people or organisations as “politically significant persons” — which would require them to regularly report political donations and arrangements with foreigners to the authorities — also creates further opportunities for surveillance, except this time the targets are press-ganged into self-reporting their activities and associations.

Placed alongside other repressive laws and policies — such as the internet gateway that the Cambodian government has already decreed will be established — an anti-foreign interference law like FICA would be yet another step in consolidating power in the government’s hands, giving them more levers to manipulate in their efforts to quash challenge and dissent.

When FICA was being debated in Singapore, the fears that civil society activists like myself had were two-fold: that the government was going to clamp down further, and that we might end up making our society more vulnerable to the very problem the government is ostensibly seeking to address.

When a country’s independent press and civil society are crushed or heavily suppressed, there are fewer actors in the game able to identify and resist foreign meddling. In Australia and Taiwan, investigative journalists and civil society organisations have been instrumental in uncovering influence operations and disinformation campaigns, alerting the public and equipping people with the skills to recognise such operations so that they can better avoid becoming victims of manipulation.

Malicious foreign interference is a real problem that countries need to be aware of and address. But when governments seize upon it as an excuse to give themselves more power and control over their people, the result is a more brittle and precarious society, not a safer one. Furthermore, foreign actors seeking to interfere in a country’s politics and policies tend to target individuals and organisations that are in positions of power to make things happen. In countries like Singapore and Cambodia, the entry points for foreign interference aren’t likely to be embattled, under-resourced civil society groups who are already dealing with hostility and repression. Instead, they are more likely to be found among the country’s establishment elite, including the very people to whom a law like FICA would hand more power.

Oppressive legislation like FICA and other controls that allow for surveillance and censorship push a society to put all of its eggs in one basket, giving people no choice but to trust those in power to behave well at all times and make no mistakes. But no political leader or party can really claim such levels of perfection and flawless judgement. That’s why we need more space for different stakeholders to carry out their work and engage in collaboration, debate and negotiation, even if this process might often seem messy. It will do Cambodians no good if their government learns from the bad example that Singapore has set.

Kirsten Han is a Singaporean freelance journalist and activist who was involved in advocating against the passage of the Foreign Interference (Countermeasures) Act in Singapore last year. She currently runs the newsletter, We, The Citizens, covering Singapore from a rights-based perspective, and tweets @kixes.