Prime Minister Hun Sen and the ruling Cambodian People’s Party continued to maintain a tight grip on power this year and showed little inclination easing pressure on political opponents and dissidents.

The CPP dominated the commune election and grabbed all but four commune chief positions, maintaining its oversized presence in the grassroots of the country. The party will now head into national election with a potential challenge from the Candlelight Party, with a party spokesperson saying they expect the opposition could win as many as 21 seats next year. It is to be seen if the ruling party is comfortable with giving away seats in the National Assembly, where it currently holds all 125 seats.

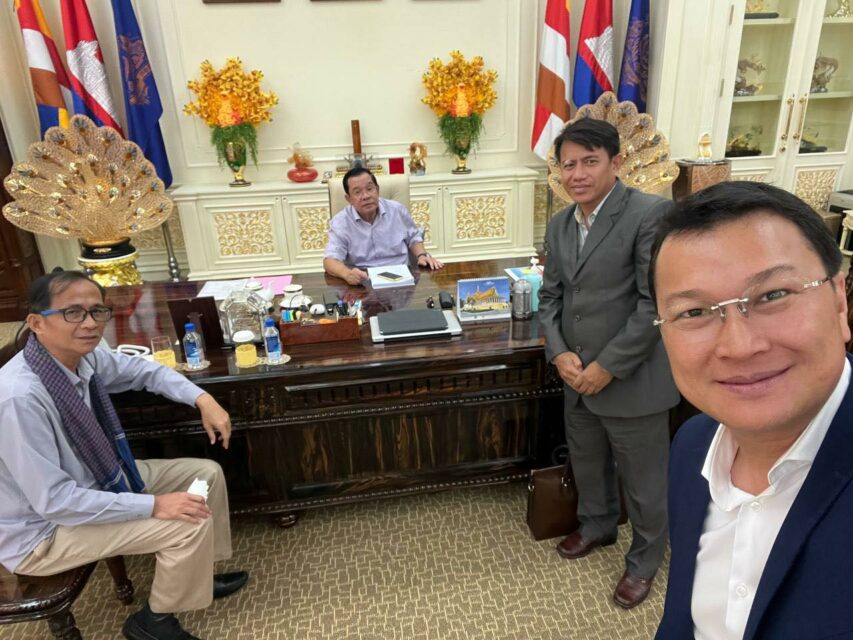

Cambodian politics is dominated by Hun Sen and his regular — and often garrulous — speeches that set the agenda and tone for the government, and much of the country. From railing against exiled opposition leader Sam Rainsy to threatening political opponents and occasionally his own party members, Hun Sen’s fiery speeches are a frequent story on VOD. So rather than going into all his politicking, we have selected a few Hun Sen’s quotes to illustrate his distinctive style and thought process.

To illustrate how anybody can be at the receiving end of Hun Sen’s pointed words, he categorically refused to be cremated at a stupa his wife built for him in Takhmao city. We will let the prime minister tell you why:

“My wife responded that she had already finished building it at Champouh Kaek, and I told her that I am sorry, I will not stay there. I absolutely will not stay there because we don’t know what things are inside the pagoda … When our ghost gets there, there will be a gangster group and I will not stay there. We spoke clearly with each other that I will not stay in the pagoda, so now my wife handed this one to my brother,” he said, referring to his surviving brother Hun San.

Opposition Suppression

Former CNRP politicians, members and activists — and more widely dissidents and opposition supporters — faced physical violence, surveillance, legal hassles and, sadly, imprisonment.

The government and courts have continued to pursue mass trials against former CNRP leaders, members and activists, with the Phnom Penh Municipal Court delivering three verdicts this year, convicting more than 100 defendants. All three cases relate to CNRP leaders Sam Rainsy and Mu Sochua trying to come back to the country, with the courts convicting anyone supporting the two overseas politicians.

After a sluggish three years, the treason trial against CNRP co-founder Kem Sokha is expected to reach a conclusion in the next three months. As the trial resumed in January, hearing after hearing followed a similar pattern: lawyers squabbling, the same evidence litigated over and over again and little substance to support the legal elements of treason. Closing arguments, which happened last week, were a marathon 10-hour session, with the court refusing to adjourn the hearing till everyone had their “fair” say. (Commiserations to those in the viewing gallery.)

Another worrying trend that has reemerged in the political landscape is the use of violence against dissidents and opposition politicians. In July, CCTV footage showed assailants getting off a motorcycle and slashing at a Phnom Penh Candlelight official with a sword, causing deep lacerations on his head. An opposition lawyer also highlighted at least 30 cases of political violence over the last five years, most with no reported arrests.

Former CNRP leader Sam Rainsy continued to attract the attention of Cambodian courts. Apart from being a defendant in all the mass trials, he was sued for allegedly promising to cede land to indigenous groups in the northeast. He also really antagonized Hun Sen when he called for the military and people to push for change. The prime minister unleashed a tirade against Rainsy and his family, calling them “three generations of traitors.”

The small bright spot for people wanting a viable competitor to the CPP was Candlelight Party’s shock emergence at the June election, where they ran candidates in almost all communes, won four chief positions and had hundreds of councilors providing some much needed oversight in local administrations. The party has shown that opposition forces can be coalesced behind a single political force, but for how long remains to be seen.

Party vice president Son Chhay got on the wrong side of the CPP and National Election Committee when he gave a media interview alleging stolen votes amid a discussion on election irregularities. He was convicted for defamation and is expected to pay the CPP a million dollars.

Small Party Watch

It was quite an eventful year for Cambodia’s minor political parties. While most made not much of an impression at the commune election in June — including previously prominent parties like Funcinpec — some experienced major changes in leadership and new partnerships, while other seemingly CNRP-aligned parties invoked the ire of the government. And of course, the birth of a political messiah.

The royalist Funcinpec party elected Prince Norodom Charavuth to lead the party, after his party and former prime minister Norodom Ranarridh’s death last year. Despite all the excitement, within the party, for their new president, Funcinpec didn’t fare very well at the commune election, continuing its downward trajectory since winning the country’s first democratic election of the early 1990s.

Next in the line of well-known minor parties is the Nhek Bun Chhay-led Khmer National United Party. The general got a reprieve in March when a Phnom Penh court dropped drug charges against him, in a 2007 case that was resuscitated in 2017 because of a purported leaked phone call between Bun Chhay and former CNRP vice president Eng Chhai Eang, where the former promised to offer votes to the CNRP in communes that the KNUP was not contesting.

The royalist general was again in the news in October when his party “merged” with the fledgling and recently formed Kampucheaniyum Party, which is run by Yem Ponhearith, former CNRP lawmaker and Kem Sokha ally. The newer party will head into the next election under the banner of KNUP, with both parties hoping to rise to being primary CPP challengers.

The Grassroots Democratic Party — which has long seen itself as a potential successor to the CNRP — started off the year saying the government was top-heavy and that its head was bigger than its body, suggesting the administration could be more efficient if it was trimmed down. Closer to the end of the year, the GDP lost one of its own heads, when vice president Yang Saing Koma defected to the CPP and joined the Agriculture Ministry to work in the long-plagued economic sector.

2022 was not a great year for Seam Pluk, who founded the Cambodia National Heart Party. He was arrested for allegedly submitting fraudulent thumbprints as part of the party’s official registration application. Pluk was expected to be on trial in November but the hearing has been delayed with no new date announced.

The Cambodia Nation Love Party was left in an absolute deadlock when a majority of its board members resigned — some of whom took government jobs. The remaining member, Siev Vissoth, tried to become acting president and call for an emergency party congress, but without a quorum of board members, as stipulated in the party’s own bylaws, and the Interior Ministry saying it was helpless in the case, he was left with no option but to leave the party in suspended animation and head to his farm.

And then we have Sok Sovann Vathana Sabung, more well-known through his flashy Facebook persona William Guang. The social media celebrity formed his own minor party and contested the 2018 national election. But this year, he was convicted for armed robbery, along with seven other defendants, for allegedly stealing three diamond necklaces, valued at around $2 million.

Lastly, the biggest party to make a splash this year — and not for their politics or electoral performance — was the League for Democracy Party. After announcing they were boycotting the elections, party president Khem Veasna pointed to “climatic aberrations” to predict the end of the world. He called on the faithful to flock to his plantation in Siem Reap, causing panic and anguish for some. However, his deadline for doomsday passed and most people left the compound, leaving him with a few hundred supporters to await the next armageddon.