By Ouch Sony, Mech Dara and Ananth Baliga // July 10, 2021

Five years ago today, political analyst Kem Ley was shot dead in the Caltex gas station at the corner of Monivong and Mao Tse Toung boulevards. A man walked up to Ley as he was drinking a Sunday morning coffee, and fired twice. The murder, of July 10, 2016, ignited one of the last outpourings of mass civic and political expression seen in an increasingly repressed nation. Recollections from Phnom Penh residents, Ley’s colleagues and others are pieced together in this account of the historic day and the weeks that followed.

Aun Chhengpor, reporter, Voice of America: I was boarding my flight — it was my first flight ever. I and another friend were heading to Bangkok. I was boarding the flight, it was a very sunny morning. I was excited for my trip. My whole family was at the airport sending me off. It was a simple, exciting Sunday at the time. I was in my seat and a member of the team that was on the flight tapped me. She was still on the phone, despite the flight attendant asking passengers to switch off their phones. She was still on her phone and told me that Kem Ley was shot.

Tim Malay, currently secretary-general for Solidarity House, at the time director of the Cambodian Youth Network: On that day, I was at an event about Mekong governance, and Dr. Kem Ley was also invited for that, but since he had just returned from the provinces, he was busy. We thought that he was tired and let him take rest.

No one immediately believed this shooting at that time.

Five minutes and 10 minutes later, we saw other news and live videos. The group and myself were in shock.

I went to Star Mart to clarify the truth.

Chhengpor: It was about 10 a.m. and I understood later that he was shot just before 9 a.m.

I last met him on July 1, 2016, when he came for a VOA interview with a colleague of mine at the VOA office in Phnom Penh. His wife, Bou Rachana, accompanied him.

I was a bit bewildered, a bit confused and could not believe it at first.

A bright sunny Sunday took a dark mode on that flight. One hour from Phnom Penh to Bangkok, there is no access to news or the internet. We still keep thinking about what happened in Cambodia — what’s next?

Sun Narin, currently a reporter with Voice of America, at the time a Voice of Democracy reporter: I was at home in the morning on July 10, 2016, and I [received a] call from my boss Mr. Pa Nguon Teang, the editor of CCIM. And he told me that Kem Ley was shot at the Bokor traffic stop. I drove my moto from home to the office, because the Voice of Democracy office is nearby the place where he was shot.

Nuth Vanny, monk, Wat Chas: When I arrived people were very crowded and they were in chaos because they were shocked.

It was very full of people and they were all over the place.

Narin: I went there. At the time, I observed people and activists coming from time to time. His wife also came. She wanted to get inside Caltex but she was not allowed to get in immediately.

Malay: There were many people and the glass door was closed.

On the other side, there is crying from family, relatives, and those who loved and supported Dr. Kem Ley.

Tears and a feeling of shock came out at the same time.

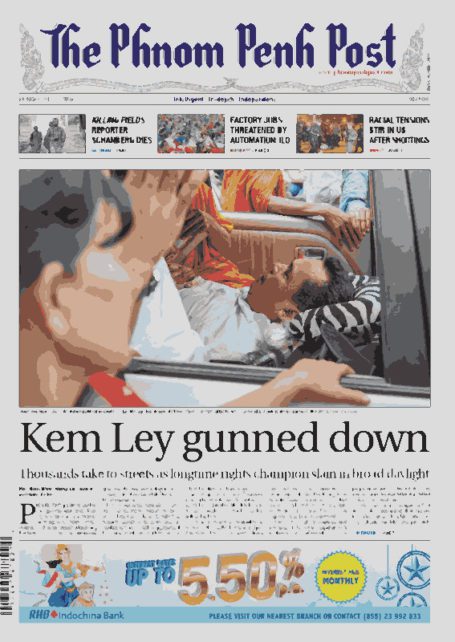

The Cambodia Daily, ‘Prominent Political Analyst Kem Ley Slain,’ July 11, 2016: Sitting alone inside the Caltex gas station at the intersection of Monivong and Mao Tse Toung boulevards, the 46-year-old was attacked execution-style, shot once behind his left ear and once under his left arm, according to Norng Sovannaroth, the Phnom Penh Municipal Court doctor.

The shooting occurred just after 8:30 a.m., according to officers at the scene. Gas-pump attendants said they thought the shots that killed Kem Ley were an electrical fault, with one staff member even flicking an emergency button to turn off the current.

“I heard the sound of something go ‘bang! bang!’ and I thought the coffee machine had blown up, because this morning the coffee machine was not working,” said pump attendant Sam Praseth, 25.

Ma Chettra, Social Breaking News: When I arrived there, my feeling was shock, and I felt pain seeing him lying on the floor in the mart. At that time I wanted to go live on Facebook, but I couldn’t speak and was choking myself sobbing.

The public were crying in front of the body. They cleaned the blood from his body and changed his clothes inside there with a cover from the public.

Narin: There was crying and people shouting at the police because the police tried to prevent people from getting near his body. So people were crying, his wife and his younger brother. Even when his body was taken, I remember people protested and said don’t take it now.

I know the police did not want to keep his body there because of the crowd and more people coming and sharing that the famous political analyst was shot inside there.

Malay: Between 11 to 12 p.m., there were many people from everywhere, and his body was removed to put in the car and sent to a pagoda on the other side of the river.

Vanny: When we tried to march him to the pagoda, there was a confrontation with [district] security guards and police, when we tried to place the body in the car. They tried to stop us, demanding an autopsy — police wanted his body to be moved to Takeo, while others wanted to keep it in Phnom Penh. So it was chaos. Others wanted to take the body to be cremated at Wat Samakki Raingsey, while others, including family, wanted to bring him to Wat Chas — they decided to bring him here. When they decided to bring him here, it was very crowded. And the sky was cloudy, but it wasn’t rain. It was like another phenomenon.

Narin: A lot of things were coming out that they had arrested a man and he immediately said that Kem Ley owed him money, $3,000. I immediately called his wife, even though I knew it was an emotional time. I called her and she denied it immediately. It’s hard.

Pov Soeun, tuk-tuk driver, 39: It looked like it was planned. I didn’t understand — a shooting in a crowd.

Malay: On that day, we did not know what to say and what was behind this.

Vanny, Wat Chas: Every day and night we held a Buddhist religious ceremony. There were so many people coming to pay their respects to him, before lunch until 10 p.m. and people lined up in four lines for about 1 km.

Because it was too crowded we had to prepare a queue to come in … since our pagoda complex is small, and because there were so many people, we were afraid there would be faintings.

People came from every province. … I noticed that civil servants came to pay their respects to him in secret — they came at night time. They came to make a contribution and they did not write their name and did not say anything. I knew it because I guarded the body until 1 or 2 a.m. and took turns to rest.

When they came, their faces were very sad, and mostly their tears fell, and they cried over losing him.

There was no invitation and they came with their heart and love and knowing him, young and old.

The Cambodia Daily, ‘CPP Media Pins Kem Ley Murder on CNRP,’ July 16, 2016: The thousands who gathered at the gas station where Kem Ley was shot dead on Sunday had little doubt about who was behind the murder of the popular and outspoken critic of the ruling CPP.

The public assassination in broad daylight had the hallmarks of hits on others who have questioned Prime Minister Hun Sen’s rule over the past 31 years, and the large crowd had no one else in mind.

Over the past two days, however, CPP-aligned media have offered a different narrative for the slaying, instead presenting the opposition CNRP — and its deputy leader, Kem Sokha — as the likely culprits.

“The question is — in this situation — who is it that would be happy with the result?” said an article on Kem Ley’s death posted to the popular and CPP-aligned Fresh News website on Monday night.

The Cambodia Daily, ‘I Am a Soldier, Suspect Said Before Kem Ley’s Murder,’ July 15, 2016: Late last week, Um Oeung received a call from his friend Oeuth Ang. It had been about 10 days since Mr. Ang up and left their sleepy village in Siem Reap province.

“I asked him, ‘What are you doing now?’” Mr. Oeung said on Tuesday, sitting outside his friend’s house after being interviewed by police.

“He said, ‘I am a soldier in Phnom Penh.’”

The next time he saw Mr. Ang he was on television, being paraded in front of the media on Sunday afternoon after being arrested for the execution-style slaying of popular political commentator Kem Ley that morning.

The man gave his name as “Chuop Samlap,” which translates as “Meet Kill,” and a video of him confessing appeared online within hours of his arrest.

Chhengpor, VOA: I called my mum when I settled down in Bangkok. Both my parents expressed their sadness because they had listened to Kem Ley on the radio and his analysis. I was worried about the people’s anger, that it could turn into instability in the city. The people were angry and protesting. I kept checking with my family and my friends how the situation felt in Phnom Penh.

Yem Vantith, tuk-tuk driver, 47: It was unbelievable. Why was it so cruel? To think the earth belongs to them and they can do anything they want. If they want you to die now, you will die now. Nowadays, we are like rubbish.

Vorn Pov, president, Independent Democracy of Informal Economy Association: People cried and felt pity for Dr. Kem Ley and they did not expect that a killer would kill him in daylight in the city.

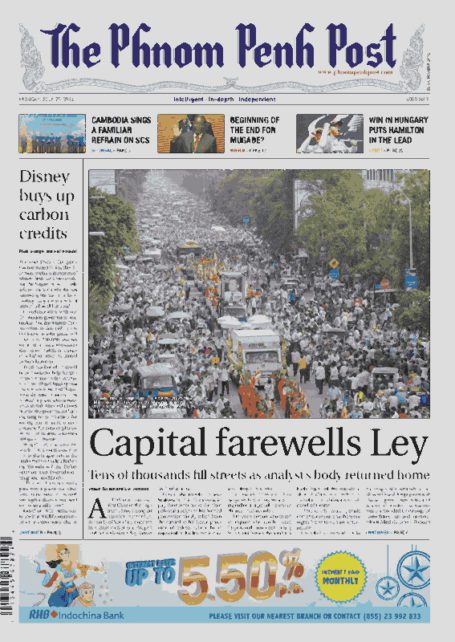

Soeun, tuk-tuk driver: The longer his body was kept [at Wat Chas], the number of people was increasing, and there was no decrease from day to day.

Vanny, Wat Chas: In our country I have not seen any funeral where there were so many people participating … even compared to the march for the former king, professor Kem Ley still drew a larger crowd than the king.

We marched his body and talked to people along the way … and they did not believe that he should have suffered like this, because he just gave his analysis in speaking out about society. They were very upset, furiously mad. And they were sorry for losing him.

Because of their love, they walked with the march, some rode motorbikes, some rode cars … there was a traffic jam from Phnom Penh to his home. We left the pagoda at 7 a.m. and arrived at the home at 10 p.m. because there was too much traffic. We phoned each other … asking whether they were in the front, middle or back — but we told each other that we did not know where the head, tail and middle were because there were so many people.

Malay, Solidarity House: I saw they were from almost everywhere, like representatives from the Royal Palace, political parties, civil societies, embassies … especially people who listened to his voice in other provinces.

Even some people who held high positions or duties did not have supporters like Dr. Kem Ley.

People held banners and cried.

Pov, IDEA: All along the way, every Cambodian cried and expressed regret. It was a historical event, in which Cambodian people expressed their sorrows.

I think it is the loss of an important human resource for the whole Cambodian nation.

Soeun, tuk-tuk driver: We could only walk slowly and slowly, and little by little, and couldn’t go smoothly even after leaving Phnom Penh city.

Starting from Phnom Penh till his homeland, people were constantly in line and bystanders and people who came out to welcome were consistently in line.

The weather was really hot but we still struggled and were committed, and though it was hot under the sun, we still could bear it and not be heated in the heart.

Narin, VOA: It was beyond my expectation that a commentator I knew and spoke to was assassinated, and I started feeling that people really loved him. It was over my expectations.

I feel like I was the luckiest person to have known him when he was alive.

Malay: He was the only person who had shown the way that society should move on.

He dared to speak what other people couldn’t speak.

Pov: He used simple words. He did not use diplomatic words or difficult words. He did not use the words for educated people. He used words for local people.

He encouraged me to be brave and be strong even when we were imprisoned. We did not need to be so afraid. He encouraged me a lot and this is the first point that I can’t forget about him.

Vantith, tuk-tuk driver: His words came out as educating, nationalism. Frankly, he loved the territory.

Chhengpor, VOA: When Kem Ley was killed it was in the midst of a political crisis already — even before the CNRP was dissolved. There were a lot of lawsuits against opposition parliamentarians, activists, even government critics.

People turned up as a show of disapproval of the politicians’ handling of the domestic state of affairs.

And they were angry. Kem Ley’s assassination united all these voices and they expressed their anger together.

Kem Ley’s killing was the beginning of the end. I mean about how Cambodia felt free to participate in politics.

Pov: It was a message for us to be strong. He said that a fish that swims along the water’s flow is a dead fish, but a fish that swims against the water is alive.

Chettra, SBN: It was historic for us. … We saw solidarity among our people.

Chhengpor: I wish I was in Cambodia with my family, with my mum. Both my parents are survivors of the civil war and Khmer Rouge. When these things happen, it reminds them of the violent past. So I think it was important for me to stay with them but unfortunately, I could not.

The feeling of seeing him 10 days before he was killed was a little bit hard to accept at first. You try to accept it as a reality, you try to reconcile with it and this is how these things happen.