Daley Uy says he didn’t even know the middle name of his friend of over 10 years. But somehow, the Phnom Penh Municipal Court attained the full name of Daniel James Capka.

An American from Texas, Capka has never set foot in Cambodia.

But last year he tagged along to Thailand with Uy, a Cambodian-American, and dozens of other supporters of Cambodia’s main opposition party, the CNRP, which was outlawed in 2017. They said they intended to join a mass march across the border into Cambodia with exiled CNRP leaders, who vowed to return to the country to “restore democracy,” and attempt to unseat long-serving Prime Minister Hun Sen following the CNRP’s controversial dissolution.

CNRP co-founder Sam Rainsy never arrived in Thailand, leaving his devoted supporters waiting on the planned return date of November 9, 2019. There was no massive “people-power” movement as promised. The party, which once stood as the greatest electoral threat to Hun Sen’s ruling party and his more than three decades in power, had failed.

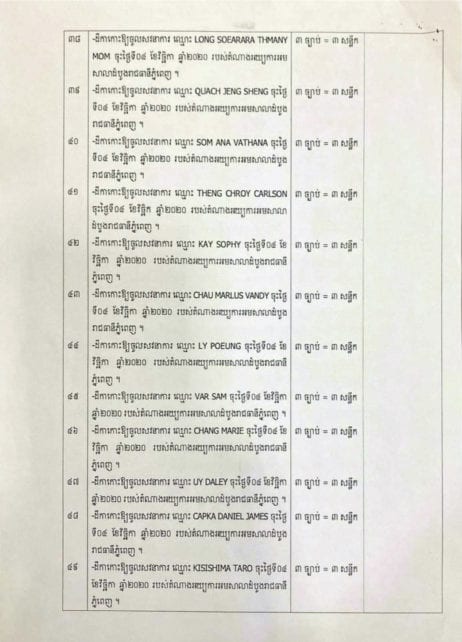

Still, the Phnom Penh court last month summoned more than 130 people affiliated with the CNRP over alleged incitement and plotting crimes related to their past opposition activism — such as gatherings in Thailand last year. Meetings of members, their Facebook posts and other public shows of support for the CNRP have been criminalized by Cambodian authorities since the party was banned at the government’s request.

In November, a day after the first hearing in the mass trial, which is set to resume in early 2021, Uy tells VOD that he has a guess of how Capka’s name ended up on the long list of charged CNRP supporters.

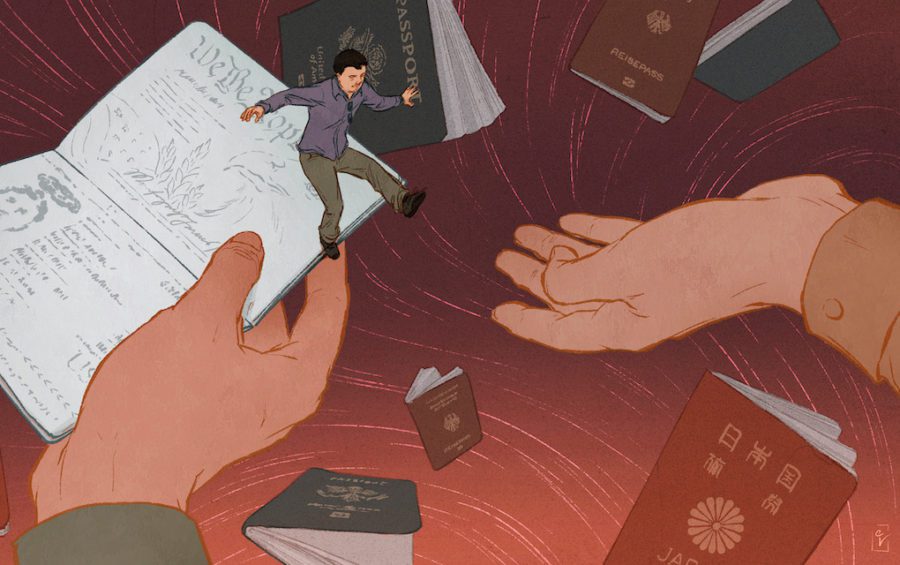

“That’s the thing that got me thinking,” says Uy, 36. “They got into his passport.”

Thai authorities who stopped Uy, Capka and at least 12 others in November 2019 in Thailand near the border with Cambodia must have shared their passport information with Cambodian counterparts, Uy says.

“How they got all those kind of names?” he asks. “I think I need to take some legal action and ask Thai officials how our names were leaked to Cambodia.”

Capka, a 58-year-old general contractor in Lewisville, Texas, says he has never been to Cambodia, never received a summons from the Cambodian court and only heard about the order to appear from Uy two days before the trial on November 26.

“I wasn’t too surprised but I really need to see the summons to see the charges,” Capka says in an email.

He was in Thailand for six days in November 2019, landing in Bangkok on November 7 and traveling with CNRP supporters to Sa Kaeo province’s Aranyaprathet, which sits across the border from Cambodia’s Poipet city.

On November 9, Rainsy, who lives in France to avoid prosecution that he calls politically motivated, was supposed to make his triumphant return to Cambodia. The day before, Capka, Uy and about 20 others were detained at a Sa Kaeo police station for a couple hours, according to Capka.

Some of them ended up being summoned by the Phnom Penh court a year later.

“At the police station [we] were photographed and fed,” he says, adding that the Thai police were “very nice to us.”

Officers even posed for a photo with Capka and one Cambodian-American CNRP supporter who was not summoned by the court alongside many of his travel companions.

But a later interaction with police in Aranyaprathet was a different story, Capka says.

“We were stopped and had our pictures taken along with photos of our passports,” he says.

They were not taken to the police station, but were held by the side of the road for about 45 minutes. Officers made Capka delete all the photos he took of them, he says.

“I was surprised that Thailand would interfere as much as they did. We were followed all the time while in Thailand,” Capka tells VOD.

On his U.S. passport, Capka’s name is listed with his surname first, then given names, or “Capka Daniel James” — the same way it appears on the summons order from the Phnom Penh court.

Asked how he thinks the court got his full name when he’s never been to Cambodia, Capka is curt: “Off my passport.”

The ‘November 9 Case’

The mass trial which Uy, Capka and dozens of other CNRP members and supporters in Cambodia and 11 other countries have been caught up in could be called the “November 9 case” for its connection to the date last year when Rainsy and other party leaders living abroad to avoid arrest were supposed to make a comeback, according to a CNRP defense lawyer.

While the day ultimately came and went without Rainsy or others making it close to Cambodia, the Cambodian government’s response was nonetheless wide-reaching, and is ongoing. More than 100 party members were charged in 2019 on various charges connected to opposition activism and organizing around Rainsy’s planned return and nearly 60 members were detained between August and November 8, 2019.

Founded in 2012, the Cambodia National Rescue Party, or CNRP, was the result of a merger of two popular opposition parties, the Sam Rainsy Party and Kem Sokha’s Human Rights Party. The joining of Rainsy, a long-time political rival of Hun Sen, and Sokha, the former head of a local human rights organization, has been seen as a means to an end: to create a larger opposition voting block that could take on the ruling Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) at the polls. The CNRP came close to winning in 2017 local elections, but was banned before it could compete in a national election the following year.

In justifying the CNRP’s dissolution, officials have accused the party and its president, Sokha, of attempting a foreign-backed coup, although scant evidence has been presented during Sokha’s still-pending treason trial. He denies the charges.

This year, dozens of dissidents have been charged and detained, many aligned with the CNRP and some who were jailed and then released in 2019.

In late November 2020, the Phnom Penh court sought ways to streamline the mass trial of more than 130 CNRP supporters in the face of misspelled names, crammed-in defendants and complaints that the accused had no information about the charges against them. Some of the accused call the proceedings a “joke.”

Of those defendants are at least 13 Cambodians with citizenship in the U.S., Germany or Japan who were stopped by Thai authorities in November 2019 in Thailand as Cambodians gathered there in hopes of joining Rainsy’s return march, according to Uy and another CNRP supporter in the U.S. who are among those summoned and briefly held by Thai police.

The presence of their names on court documents — 23 written in English — and the fact that some did not even enter Cambodia within the last year have raised suspicions among some of the accused that Thai authorities gathered their names or passport information and sent it on to Cambodian authorities.

Cambodian officials said they did not know or did not answer questions about whether Thai authorities had passed on names or passport details. A Thai Foreign Affairs Ministry spokesperson did not reply to emailed questions.

Three CNRP supporters, as well as Capka and a CNRP vice-president, allege that Thai authorities must have passed names to Cambodian counterparts after they were held while driving toward the Thailand-Cambodia border, with authorities taking photos of them and their passports. Observers also suggest that cooperation in disrupting opposition political activities between Cambodia and Thailand is likely.

‘Get Us to Be Cambodian Traitors’

Uy, a 36-year-old fiber optic technician, says he never received a summons at his home in Dallas, Texas. He learned that he was charged from a Cambodian-American friend who sent him a Facebook message on the morning of November 14. Images of the court documents had been circulating online.

When Uy told Capka about the summonses, Uy recalls that his friend just laughed.

“We both know they don’t have no jurisdiction on us,” he says.

“We go there, and both of using American passports, and they try to get us to be Cambodian traitors,” Uy adds, laughing. “It’s just crazy.”

“Of course, I know it’s a joke. It’s all nonsense, they just put our name on there,” he continues.

“They just try to scare us not to join any political action with Sam Rainsy,” Uy says. “But what they don’t know is we already [made] our commitment before we go to Thailand last year.”

Uy and another Cambodian-American together confirmed that 13 CNRP supporters on the court summons lists, including themselves, plus Capka, had been stopped by Thai authorities in November 2019 and had their non-Cambodian passports taken and then returned by police.

Asked whether German passport holder Kay Sophy, who was summoned as part of the mass trial, was at the Thai police station, Uy says she was there.

Another German, Phu Thida.

“I know I saw her there.”

American Kim Annie Thach.

“I saw her there.”

American Ana Vathana Som.

“She’s there.”

Another American Sam Var.

“He was there.”

‘Trading Favors’

Political observers in the region describe cross-border cooperation between Cambodian and Thai authorities like a dissident exchange scheme.

Paul Chambers, international affairs lecturer at Naresuan University in Thailand, says he doesn’t have evidence, but could surmise that Cambodian and Thai authorities collaborate on law enforcement and security matters related to opposition political activities.

“Since 2014 the Thai and Cambodian governments have worked closely together to return dissidents to each other,” says Chambers, who researches civil-military relations in Southeast Asia.

He says it is “very likely” that Thai police, who stopped, questioned and photographed CNRP supporters in Thailand in November 2019, sent their passport information or names to Cambodian authorities, although again he has no evidence.

In helping the Cambodian government control potential opponents, Chambers says “the Thais are expecting in return that the Cambodians will arrest Thailand’s regime opponents.”

Thailand is known to have extradited a number of Cambodian government critics after they fled there from Cambodia in recent years.

In June 2020, Thai pro-democracy activist and government critic Wanchalearm Satsaksit disappeared and was allegedly abducted from outside his Phnom Penh condominium building, although Cambodian officials have questioned whether he was even living in Cambodia and insisted that authorities had pursued all available leads. Rights groups have expressed doubts over the investigation.

Wanchalearm’s sister arrived in Cambodia in November seeking answers about her brother’s disappearance and testified during closed-court hearings in early December. She told reporters she aimed to show the Cambodian government that her brother was indeed living in Phnom Penh at the time of his disappearance.

According to Chambers, security agreements between Thailand and Cambodia also include Laos, Vietnam and Myanmar.

Phil Robertson, deputy Asia director for Human Rights Watch, agrees that Cambodian and Thai authorities have a history of cooperation when it comes to policing political opponents.

When Cambodia wanted specific people in Thailand to be detained and returned, they knew who to talk to in the previous military junta, and the relationship has continued under Thai Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-ocha’s government, Robertson says.

“This is about trading favors, almost like a sort of swap mart for political exiles and refugees between the two sides,” he says in an email.

Asked about the brief detention of CNRP supporters in Thailand in November 2019, Robertson confirms that some were held by Thai police near the border, and had their passports and other documents inspected.

“A number of those exiles and their supporters contacted Human Rights Watch for help to get them released, and we did what we could — but ultimately, the Thai authorities released everyone and sent them to Bangkok,” he says.

Human Rights Watch never saw a final list of all those detained in Thailand, and has “no information to indicate that information was passed to the Cambodian side,” according to Robertson.

But he says it would not surprise him if information was passed to Cambodia.

“If the Cambodian authorities contacted Thailand and urged them to intervene, that would be enough for such actions to take place,” he says, adding that the Thai government had made it clear at the time that CNRP leader Sam Rainsy was not welcome in Thailand and would be turned around if he tried to fly into Bangkok.

‘No Way the Court Could Have Known’

CNRP defense lawyer Sam Sokong says most of the accused in the November 9 case were charged with incitement and plotting an attack over party activism — from taking group photos, to creating Telegram and Facebook Messenger chat groups — linked to the CNRP plan to welcome Rainsy and march with him to Cambodia in 2019.

An incomplete list of the summoned CNRP supporters provided by the party’s vice-president, Mu Sochua, says 28 of 113 people are in Cambodia, while 71 are spread across 11 countries. Some people’s locations were not given.

Seventeen of those summoned are in South Korea, 15 in Thailand, and 13 are in the U.S., according to the list. Many CNRP leaders and party activists fled Cambodia in fear of arrest following the 2017 dissolution of the party.

“Those in South Korea never came to Cambodia but they joined [opposition] meetings or protests, and they were charged with plotting,” Sokong explains.

The lawyer says the 34 defendants present in court for the first hearing on November 26 were the people who were in Cambodia. He estimates that about 70 to 80 summoned CNRP supporters were living overseas, or more than half of the total.

As of the first hearing, 50 to 60 people had asked Sokong to represent them in court. Some in the U.S. had sent letters requesting his representation.

By the next scheduled hearing in January, the attorney says all of the over 130 people might ask him to defend them.

“Most of them show willingness to participate. They said they have made no mistakes. They want to show their innocence,” he says.

It is not necessary for the summons to be given directly … this is the legal principle.

The CNRP’s Sochua, who lives in the U.S. and was not able to travel to Thailand last year after a number of senior party leaders were blacklisted by the Cambodian government, says she believes Thai authorities passed names of CNRP supporters from abroad to Cambodian counterparts.

“There is no way the court could have known their names but not their current addresses,” she says. Addresses were not included in publicly released court documents, although it is unclear if the court obtained the addresses of those summoned who are living abroad.

Court spokesperson Kuch Kimlong did not reply to multiple requests for comment.

Sochua, who faces charges of her own, calls the mass trial a “total mockery of justice,” and again called for the Cambodian government to return her and other senior CNRP leaders’ Cambodian passports, so they could travel back to the country to stand trial and defend themselves. Their passports were voided by the government in November 2019.

“There is no single attempt of fair trial and due process. We are innocent,” she says. “It is the courts’ [job] to find our guilt. Not to consider us guilty as charged.”

‘Nothing Strange’

Asked how the court was able to identify the full name of Daniel Capka, Justice Ministry spokesperson Chin Malin just says it was the authorities’ duty to investigate crimes so they have all necessary background information.

“Who is involved, and when they are involved, what are they doing? And what are their names and where are they? All this is [part of] the investigation of the authorities,” Malin says.

A trial involving such a large number of defendants is not unusual, he adds, because sometimes more people are involved, especially when offenses are committed by a structured organization, acting in a systematic way.

“This kind of offense has more people involved, including conspirators, plan organizers, supporters, the plan practitioners, the aid supporters — all are involved and based on the Criminal Code, those who were involved and participated have to take the same responsibility in accordance with the law,” Malin says.

“So, having more people involved is nothing strange.”

Following complaints from some accused CNRP supporters, including those living overseas, that they never received court summonses, Malin says authorities could use “all means” to disseminate the message that people needed to appear in court — from publication in media to posting hard copies at the CNRP’s abandoned former headquarters in Phnom Penh.

“It is not necessary for the summons to be given directly [to the individual], but [they] can get information and news from the summons by all means, and this is the legal principle,” according to Malin. “Whenever we get information and news, it is considered that the summons has been delivered.”

Interior Ministry spokesperson Khieu Sopheak says he does not know when asked whether Thai authorities had sent the passport information of summoned CNRP supporters to Cambodian authorities.

National Police spokesperson Chhay Kim Khoeun declines to answer when asked whether Cambodian authorities had requested information about CNRP supporters from Thai counterparts, and about how someone who had never been to Cambodia ended up being charged.

“It is beyond my jurisdiction to reply because I am not the one who issued the summons. The court prosecutor issued it,” Kim Khoeun says.

Asked if there was any cooperation between countries in sharing information about suspects, Kim Khoeun says “there are mechanisms starting from the government level, law enforcement level and the border authorities level.”

“Generally, cooperation is not just with Thailand. It is international,” he adds, citing Interpol efforts and cooperation in searching for escaped offenders.

‘I’m Number 39’

Jeng Sheng Quach, a 67-year-old retired machine operator living in the U.S.’s Vancouver, Washington state, emigrated to the U.S. in 1982 as a refugee. He says he last visited Cambodia in 2017, when the CNRP nearly defeated the ruling CPP in commune elections.

Later that year, the Supreme Court dissolved the CNRP, banning the main opposition party from competing in the 2018 national election. The CPP then won all 125 parliamentary seats on offer, making the country a de facto one-party state.

Quach says Hun Sen did a “really cheap thing,” accusing the prime minister of dissolving the CNRP because he was afraid.

Three years later, in mid-November, Quach learned that he had been summoned after the court orders were posted on Facebook.

“They want us to go to the court. We’re not even in Cambodia,” he says. “The court is a joke.”

On the summons list, he says, “I’m number 39.”

Many older Cambodian refugees, like Quach and others, who immigrated to the U.S., Europe, Australia and elsewhere after the overthrow of the genocidal Khmer Rouge regime in 1979, today support the political opposition in Cambodia, seeing Hun Sen and his long-ruling CPP as authoritarian.

Another CNRP supporter who also was held by Thai police in 2019 and charged in 2020 says he too received no summons, and had committed no crime.

“[The court] charged me for plotting. What plotting did I do?,” says Kirishima Taro, 68. “Incitement is only when we use our voice. I have never held any microphone to incite [anyone] at all.”

Kirishima, a Cambodian-Japanese man who works in a turbine factory, says he also learned about his summons from a Facebook post.

The court did not spell his name correctly on the order, yet Kirishima can think of no other way the court could have gotten a near match to his name, which was written in English on the court document, than via Thai authorities who had collected his passport.

“If Thai [authorities] did not send [my passport] to [Cambodian authorities], how can the Cambodian court know, because I had not met with or been checked by Cambodian police?”

His last visit to Cambodia was in 2016.

‘In the Blacklist’

On December 1, Capka says he’ll share some photos from his trip to Thailand, and also makes a request.

“Do you have an English version of the summons/indictment? I would be interested in the specifics of the charges against me,” he says in an email.

No official English version is available, but a reporter lets Capka know of the likely charges against him — incitement or plotting — both of which carry prison terms if convicted, and shares an English copy of Cambodia’s Criminal Code.

Uy, Capka’s friend, says he never even entered Cambodia in November 2019. The last time he was in the country was January that year for a family visit.

Now, Uy says he will not return to the country unless there is a political agreement between the government and opposition leaders, and the “political heat” goes down.

“You kind of feel that you’re in the blacklist with the Hun Sen government,” he says. “It’s considered not safe to go there [to Cambodia].”

However, if CNRP leaders attempt to return to the country and face the court, which they have vowed to do in early January 2021, Uy says he would join them.

The party’s end goal, he adds, is free and fair elections in Cambodia.

For Capka, he seems less certain about any future travel plans. He probably would not visit Cambodia until the charges against him were dropped, he says.

“As far as concern about the Kangaroo court, I guess I’ll see how it pans out.”

This article was produced by New Naratif and VOD, who have partnered to publish long-form journalism from Cambodia that empowers our shared community with news and information.