ANLONG PHE COMMUNE, Stung Treng — In early March, Auon Seap noticed a group of unknown men approach his farm on a koyun, an elongated tractor mostly used for farming or logging. Strangers are not so common in his village on the northeastern edge of the Prey Lang Wildlife Sanctuary.

The 25-year-old farmer asked what they were doing after he noticed that the group was tilling dirt and destroying his potato crop, which grows well in the hilly terrain of Seap’s plantation in Stung Treng’s Toal community protected area.

“I was feeling sorry about my plantation, so I told them, ‘Oh you’re cutting up my plantation,’” he told VOD in May. “The group responded, ‘We will cut more than that, we will make a road and also a power line over here so [your plantation] will be gone.’”

Electricite du Cambodge, the country’s sole electricity utility provider, announced plans in 2020 to develop a transmission line from the border with Laos in Stung Treng that tracks south to Phnom Penh, and commissioned Cambodian firm Schneitec Group to build it.

Residents living in and around the 640-hectare Toal community protected area say the electricity authority is starting to mark the path of the power line, which will cut across the Prey Lang Wildlife Sanctuary. Schneitec has yet to provide information about potential impacts to the forest and compensation for land lost.

Conservation groups warned at the time of the power line’s approval that such a development would fragment Prey Lang Wildlife Sanctuary, one of Cambodia’s largest evergreen forest landscapes that’s already facing large scale deforestation as well as a proposed 938-hectare mining project that could further exacerbate forest loss.

“The proposed transmission line route would effectively divide PLWS into two by creating a road that transects the entirety of PLWS,” said Matthew Edwardsen, chief of party to USAID’s $21-million Greening Prey Lang project, in 2020. “This would result in significant fragmentation of PLWS evergreen forest.”

The Direct Route

Community chief Mao Nov and a few of his colleagues stand in a thinning patch of forest at the edge of their protected area in Anlong Phe commune in May. The road is wide enough only for a motorcycle. They point at iron rods sticking out from the ground, one of their ends spray-painted red.

Electricity supplier EDC put these markers across Prey Lang to indicate the transmission line’s path, they said.

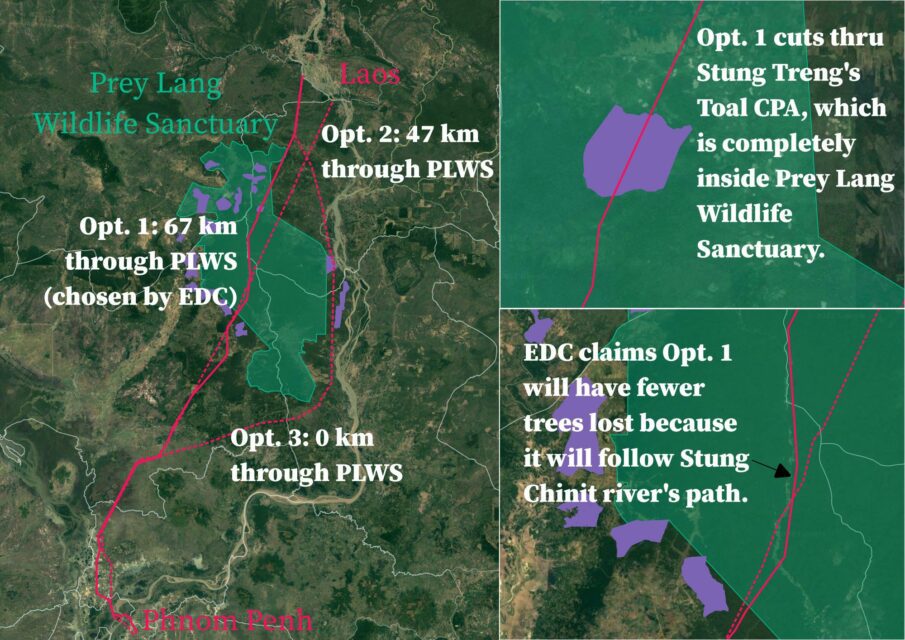

A PowerPoint presentation of an environmental and social impact assessment for the project, drafted by consultancy firm SBK and seen by VOD, assessed three possible routes for the transmission line: The first route cuts through 67 km of Prey Lang, a second option cuts across 47 km of the sanctuary, and a third would skirt the protected area.

According to the presentation, SBK recommended the first route, which would cut through the most area of Prey Lang, because it would require cutting fewer trees than the other routes and also cost less.

The report says the longest route follows a river and would require cutting the fewest trees. It also presents three pricing options for the proposed routes: The cost of the longest route through the forest is estimated around $228 million, or $32 million less than the route that doesn’t cut through the protected area at all.

The report says the government would have to displace more people from their land if the power line went around Prey Lang, increasing costs of compensation and affecting the total price of the project. The presentation does not touch on potential impacts on wildlife by splitting the sanctuary in half, and does not mention potential effects on community protected areas.

The report emphasizes the benefits of the project, claiming the operator would initially not pay tax but would begin sharing profits with the government once the transmission line started earning money.

Schneitec, the electricity company contracted to prepare the project, has been linked to a sibling of Keo Rattanak, the chairperson of EDC.

Chhun Delux, deputy chief of forest carbon credits at the Agriculture Ministry, said in August the project had already been approved by EDC and the path was marked out, but he did not know when construction would begin.

“As I understand, one community forest is crossed by the transmission line, they already agreed and they had concerns,” said Delux, who is also director of one of Prey Lang’s two Redd+ carbon credit projects.

Residents of a community forest called Choam Smach had accepted the route for the power line, he said, and estimated that the community would be paid about $1,000 for every hectare that the power line crosses.

“The funding is being transferred,” he said, explaining that it would take time for CPA teams to receive compensation because an account would need to be established.

“But for Prey Lang, we don’t have any information, but as I understand it, the long line has been laid across Prey Lang Wildlife Sanctuary and a lot of evergreen forest will be cleared through Prey Lang.”

The announcement of the project was enough to draw some opportunists in the community, Delux said.

“We learned that [along] the new line, small-scale forest clearing has been happening, people around the field and around the forest heard the transmission line will be approved and they’ve been going to clear land,” he said. “They believe that they can access electricity in the future.”

Jackson Frechette, Greater Mekong landscape manager for Conservation International, said he had not heard any updates about construction of the transmission line as of August. The international environmental group oversees one of two Prey Lang carbon credit projects.

Poles in Toal

Mao Nov, Toal’s community leader, is frustrated with the meager funds the protected area receives. Despite this, they have had some success in stopping individuals from logging their protected area, he said.

“There are some [people] cutting the trees for wood, [but we] only patrol in the community’s forest … sometimes we see people cutting trees to make a house, but it’s rare to see a bigger case,” Nov said.

Nov said he and other patrollers have set up a system where they urge residents to ask permission to take timber from the forest for a new house and when granted, cut a limited number of trees. He claimed that people were respecting the system and fewer people were cutting trees recklessly.

But earlier this year, he saw a group of people going into the forest on a koyun, and then he heard rumblings about the power line from residents in the community.

“I only know from people around” the forest, Nov said. “Even the village chief doesn’t know about this.”

When asked if he had contacted the commune or district authorities about the project, he expressed dissatisfaction. “How can I contact them, because I also don’t have the information?”

He added that there had been no construction activity since the EDC representatives came to Toal.

Nov had only heard rumors about the power line project, but if it went ahead as planned — a proposed 40-meter wide clearing and a road along the power line — it would hurt the Toal community protected area and larger Prey Lang forest.

“The forest will be lost because this is huge,” he said.

Kong Dim, a member of the Toal CPA committee who met with reporters at Nov’s house, said he had helped guide EDC officials into the forest when they first came to demarcate the power line’s path, taking them as far as the remote area of Spong, a village in Anlong Phe commune on the border of Preah Vihear and Kampong Thom provinces.

“It was last year, October, when I brought them there, and I asked when they wanted to build and EDC said it would be built this year. But this year from January until now, I haven’t seen it,” Dim said in late May.

Dim worried that changes to the terrain would harm animals that live in the forest and also suspected it would impact community members, many of whom were living on state land and did not have land titles.

“At first I was happy to have a power line, but later I would say I’m not very happy because it will affect the people who have small land and a lot of trees will be cut down,” he said.

“People don’t have land titles, it’s state land, so if they don’t give compensation, what can people do?”