Alex* was helping his stepson pack supplies late last year, in anticipation of Sonny’s* new job in Cambodia. Sonny was leaving their hometown of Hsinchu city in Taiwan hoping for better wages and opportunities, but he and his stepfather knew little about what to expect in Cambodia.

Looking back, Alex, who is a 58-year-old sales director in Taiwan, thinks he should have looked more closely at Sonny’s job contract or asked about the friend who lured Sonny with the job and a promise of a high salary.

After crossing into Cambodia, Sonny worked at an online investment firm convincing people to follow the firm’s “teachers” in pursuit of high returns. But a few months after being in Cambodia, Sonny realized he was trapped at a mega resort complex in Koh Kong with little hope of leaving.

Sonny’s story is similar to dozens of accounts told to VOD where foreign nationals from Thailand, China, Malaysia, Vietnam and other countries are forced to work at scam operations, forcibly detained, and often beaten or tortured, with little to no intervention by local police and authorities.

Meeting a reporter in Phnom Penh in early June, Alex regretted that he didn’t look closer into Sonny’s job offer. “I thought [there was] something weird, but his friend had this experience [abroad] so I didn’t doubt it, that it was this kind of organization,” he said.

When his 32-year-old son said he couldn’t escape his work, Alex flew to Cambodia in June to try and get Sonny out. Alex headed straight to Koh Kong province’s Union Development Group concession, notorious for brutal evictions and environmental destruction. The project has also been sanctioned by the U.S. government for alleged Chinese military operations.

Alex first attempted to rescue his son by filing a complaint to Koh Kong police officials, with reporters accompanying him to observe the process. Previously, immigration and law enforcement officials have urged family members to first file an official complaint of potential forced detentions.

So Alex brought his son’s case to the Koh Kong police in early June. But hours after he filed the complaint with the police, details appeared to have been leaked to the scam syndicate’s boss in Botum Sakor province.

The 32-year-old Taiwanese national was eventually released from the scam company, but only after he said he paid more than $7,500 to the operations. The stepfather and son were reunited but not before they were put through an ordeal many families have to traverse to have any hope of rescuing their loved ones from scam syndicates in Cambodia.

Since Sonny paid his way out of the casino, more reports of Taiwanese nationals trafficked to and detained in Cambodia are flooding news outlets, and politicians have sought cooperation from Cambodia as well as China to rescue victims and investigate cases. Other cases of foreigners detained within the Union Development Group concession have since surfaced, with the Philippine Embassy last week publicly requesting Cambodian officials to rescue four of its nationals from a company on the fourth floor of a building near Long Bay Casino.

Concessions and Scams

In the first few months of Sonny’s job, Alex said he heard very little of his son’s work.

“When I asked him, what about your job, he’d say ‘I’m very tired,’ something like that,” Alex recalled to reporters. The most he could get out of his son was that the work was related to “virtual money,” or investing online in cryptocurrency. “For three or four months it was like this.”

When he returned to Phnom Penh after his release in June, Sonny recalled that he had initially gotten a job in Sihanoukville, with the help of his friend, a woman he went to university with who he named as “Ms. Chen.”

According to Sonny, Chen worked in casinos in the Philippines for several years before coming to Cambodia, where she started telling Sonny of the money he could make working abroad.

Sonny had worked as a delivery driver in Taiwan before, and was interested in earning more than $1,000 a month. He left for Cambodia in December to work at a job Chen had found for him.

Sonny started working to promote an online gambling firm in Sihanoukville, though he was unsure which compound he worked inside. But Sonny remembers his task: sending texts and making calls to cell phone numbers supplied by the company’s automated program, and asking Chinese speakers if they wanted to learn from “teachers” how to invest their money.

If they responded in the affirmative, he would pass their information to a more senior team member, though he claims he didn’t know what these “teachers” would do.

“In the company there would be people, they call them teachers, to help the clients make money first, but I thought it wasn’t right to make money so easily, I felt like these people would get scammed later,” he said.

After around three or four months, Sonny approached his boss and asked to leave. He had never been able to step outside the building except with a supervisor, and was told he’d have to pay a fee of over $2,000 to leave. The boss said the fee was to recoup what they spent on his flight ticket, visa and other expenses. So he used the salary he had earned in the job to pay his way out.

Sonny said he had wanted to go back to Taiwan, but Chen, the friend who brought him to Cambodia, asked him again to help another colleague to expand the team in another company.

The 32-year-old agreed, despite having just worked at one scam operation recommended by Chen, and found himself in Koh Kong province to work inside one of the most fraught land concessions in Cambodia, developed by the Union Development Group.

This time, Sonny’s new employer was operating a classic romance scam: Workers would chat up people on social media, and slowly introduce ideas of investing into a rigged cryptocurrency platform, which Sonny said was changing currencies and URLs constantly to avoid detection.

Sonny claimed he was bad at luring people into conversation, and that only a few of the dozens of people he spoke to had invested in the cryptocurrency platform. Because he could speak some English, Sonny spent more time managing a team of South Asian workers as they collected social media accounts of potential victims.

Sonny said these workers were looked down upon by Chinese bosses. He initially said no one was beaten, though later alleged he had seen a man getting tasered. The threat was always there, as one of the supervisors was a more muscular man who often wore a scowl, he recalled.

Within a month of arriving, Sonny wanted to leave, especially after hearing that his grandfather was on his deathbed. Sonny asked his boss to leave the Union Development Group compound, but they ignored and refused his requests.

In April, Sonny’s grandfather died. Unable to meet his dying grandfather, Sonny started sharing more details about his work and location with his stepfather, Alex.

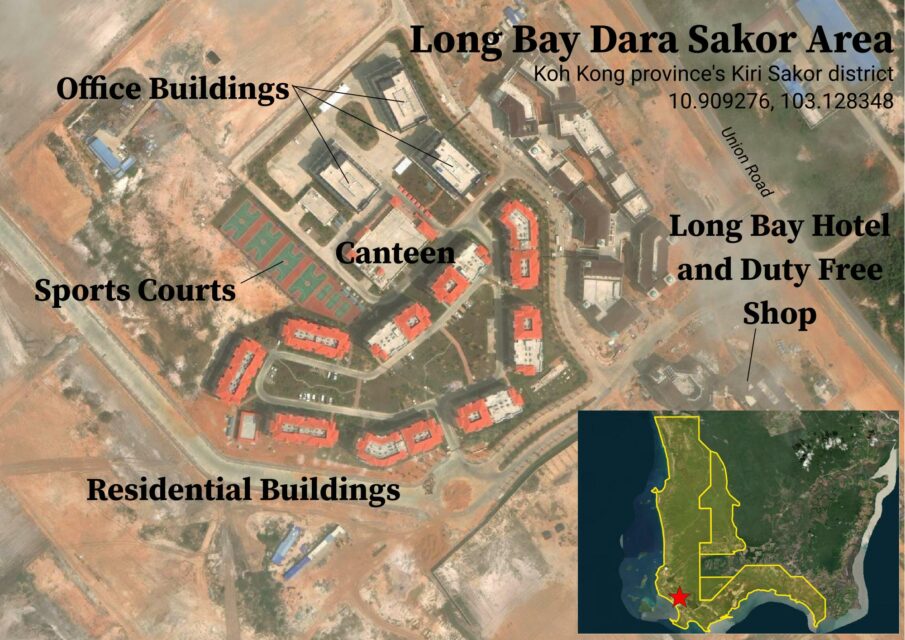

Alex came to Cambodia with several maps of Cambodia and printed photos showing different angles of the compound from Google maps. Through sporadic messages on the chat application Line, Alex and his wife identified a building and room numbers where Sonny slept and worked, in a building complex just behind the resort and duty-free shops of the Long Bay project.

Long Bay is a tourism and infrastructure project within the Dara Sakor concession and is being developed by ZhengHeng Group, a Cambodia-based company chaired by Chinese nationals with relations to the son of a deputy prime minister.

When his son initially started explaining he was stuck in the compound, Alex said he was not sure how to proceed. He said he contacted a local senator in Hsinchu city, and they did not respond. Taiwan also does not have an embassy in Cambodia, eliminating one route that other foreigners have used to request extraction from compounds.

He also contemplated breaking into the compound himself, though he had never been to Cambodia.

“At the first moment, I just wanted to go [to Cambodia] myself to help him out,” he said.

Alex started to plan a trip to Cambodia, while his wife got in touch with a Taiwanese YouTube content creator called “Bump.” The social media personality makes videos about gambling and scam companies for a Taiwanese audience.

They also connected Alex with an international scam victims’ advocacy group called the Global Anti-Scam Organization to help research the case and attempt to rescue Sonny.

The Rescue Attempt

Reporters accompanied Alex to Koh Kong province in early June as he filed the police report. Through a connection from Bump, Alex consulted with the Taipei Economic and Cultural Office in Ho Chi Minh City, which functions as de facto consulate given Taiwan’s controversial diplomatic status under China’s shadow.

A representative in the office wrote and signed two letters for Alex to present to Cambodian authorities — provincial police chief Kong Mono and provincial governor Mithona Phouthorng — asking them to remove Sonny from the concession.

When Alex arrived at the provincial police department, he was directed to different offices before being led to the immigration department at the back of the building, where one officer spoke Chinese and translated to a superior.

Alex explained his son’s case, and while police were familiar with similar forced labor cases, they initially defended the company at Dara Sakor.

Police officials, who often outright reject the existence of these cases, occasionally will categorize requests for extraction as a labor or contractual dispute. They have previously also denied that any evidence exists to support the claims or torture and beatings inside these compounds.

The superior officer, who spoke Khmer, asked Alex if his son was on a work contract, and then explained that if his son is on a six-month contract, he can’t leave until that time has elapsed.

“He wants to leave but he cannot leave. If he wants to leave, he has to pay the money because he has not finished his work contract,” he said.

The official added that in his experience, these companies don’t torture or abuse workers, and they have meals and breaks but are not allowed to leave the work compound.

When a reporter asked if workers have the right to quit and leave the compound, the officer agreed but said the workers owe the company.

“They are allowed to work there but they cannot let them get out and they do not beat or hurt them, they just stay in one block [of buildings],” he said.

The officers then asked everyone but Alex and the YouTube creator to leave the office and wait outside. After an hour, Alex walked out with a copy of the police complaint, saying he believed his son would be out of the compound, maybe before the end of the day.

“When I went out of the police office, I felt a lot of hope,” he said, reflecting on that initial interaction with police. “When I went out of the police office, I feel that, OK, we succeeded, but at the night, around 5 p.m., I thought, ‘OK, we f— up.’”

Throughout the afternoon, Alex said he and his wife were texting each other and the Mandarin-speaking Koh Kong police officer via WeChat: The officer asked for a recent selfie of Sonny, but Sonny didn’t immediately respond. He sent a selfie later in the evening, where Alex said he looked very scared.

Sonny later recounted that he was interrogated twice that afternoon: first with one friend who worked at the same operation, and later on his own. He says he wasn’t beaten, but one of the two supervisors who questioned him was stern and muscular, and he had previously seen the supervisor taser a Chinese worker for disobeying orders.

They began asking Sonny and his friend who they knew in Vietnam, without any prompting from Sonny. The two supervisors also interrogated the men separately. They let the friend go when they saw he was not involved in the rescue, Sonny said, but questioned him for more than an hour.

“In the end they knew someone went to the Taiwanese [consulate in Vietnam] to get this document,” Sonny said of the letters from the Taipei Economic and Cultural Office in Ho Chi Minh City for Cambodian authorities.

Alex added: “I think they had this document because the police officer took a photo already.”

Sonny then communicated this back to his parents, and claimed he heard the supervisors planning to transport him to Sihanoukville. Sonny’s mother, back in Taiwan, was distraught when she heard this, sobbing on the phone to Alex until late in the evening.

Around 9 p.m. that night, Alex began talking to Chen, the friend of Sonny who lured him to Cambodia seven months before and seemed connected to the company in Long Bay.

Chen offered to help Alex get from the provincial capital Khemara Phoumin to Dara Sakor to try to reach his son, sharing a contact of a driver who could pick him up that night. But when Alex told her that he had visited Koh Kong with reporters, the friend warned him not to bring journalists along.

Alex began telling reporters he wanted to go to Dara Sakor that night, and reporters warned that it would be difficult to arrange and potentially dangerous at night. He bought a hammer in Khemara Phoumin city, the capital of Koh Kong province, saying he wanted to protect himself against stray dogs but that he could also use it against an attacker.

Alex stayed in Khemara Phoumin that night and hired a driver the next morning to go to Long Bay resort, he told reporters — who did not join him on this trip.

Sonny and Alex later recalled to reporters that the former’s boss told him he could leave if he paid $7,530, which the boss claimed covered the employee’s expenses during his time in Dara Sakor. Sonny paid the ransom, claiming he again used his salary plus borrowed money from friends in Taiwan. He was released before noon the same day and wandered around the premises snapping pictures of the resort and trying to stay out of sight.

Alex arrived around 1:30 p.m., quickly loaded Sonny and his luggage into the car and sped away from the UDG concession.

The UDG Concession

Sonny knows the name of the scam operation he worked at inside Long Bay resort. The operations employed a few dozen Chinese nationals and other foreigners to run different stages of the romance scam.

However, he did not want to reveal the operation’s name because one of his friends was still inside the company and would potentially find it hard to escape. Sonny revealed some details about the operations within the Long Bay-based company, where he could move between buildings of the scam operations but rarely brushed against tourists, who were visiting the complex’s entertainment and shopping buildings along the main road.

Sonny said he and his colleagues lived in buildings behind the Long Bay resort complex, but they could still see tourists arrive in branded buses, different from the vans and SUVs that usually brought workers into the compound.

As somewhat of a supervisor himself, Sonny explained that South Asian workers were a newer addition to the detained workforce inside his company, but there were separate brokers who brought them in and sold them to other companies.

He said brokers would visit his company sometimes to test the typing speed of South Asian workers, who were doing the preliminary jobs of finding potential scam victims, especially among English speakers online.

ZhengHeng has been promoting the Long Bay Dara Sakor tourism resort, which spans 200 hectares within the 45,000-hectare concession granted to Union Development Group since 2008. According to its website, the company aims to host a population of 80,000 in this one resort, and ZhengHeng advertised an “intelligent industry park” on 55 hectares of the resort area, in addition to tourism offerings.

ZhengHeng Group is directed by two foreign entrepreneurs, Zhou Guiqin and Deng Pibing. While Zhou only appears to be connected to ZhengHeng, Deng has past or present directorships in 21 companies in Cambodia, as well as citizenship, according to a 2016 government announcement.

ZhengHeng Group also posted that its subsidiary, ZhengHeng Development Group, invested in the Long Bay Duty Free Shop, Long Bay Century Hotel, and Long Bay Casino Hotel — the latter was where Alex picked up Sonny in June. ZhengHeng Development Group is directed by Deng and Wu Jianfeng, who appears to be a director on at least two other businesses called ZhengHeng.

On the group’s website, it lists seven other companies under its organizational chart, including BIC Commercial Bank, BIC Security, a job hunting platform called CamHR, and internet service provider Cambo Technology. BIC Commercial Bank and BIC Security are also directed by Yim Leak, a tycoon who controls financial companies as well as Sihanoukville’s Queenco casino, and is the son of deputy prime minister Yim Chhay Ly.

Sonny also explained that he got his salary in cash, but he would use a payment app called Long Pay for some small purposes like buying phone credit.

The website for Long Pay lists an address in Phnom Penh’s Koh Pich island, as well as an email address for someone named Roy Liang.

Roy Liang is also listed as the special assistant to the director of ZhengHeng Group, which is a developer for the Dara Sakor project in Koh Kong province.

Tourism and residential products inside the concession are also being promoted by Coastal City Development Group, formerly known as Union City Development Group. The group’s Phnom Penh office is promoting a separate tourism development called “Stardream Lake Tourism Town,” which appears to be on a different piece of land within the expansive concession.

The Cambodia-based company, directed by a Chinese national named Li Mengchen, is a subsidiary of Tianjin Youlian Development Group. The group was reportedly represented by Li Zhi Xuan at the time the concession was granted by the Environment Ministry in 2008, and Li has a certificate of a $20,000 donation to the Cambodian Red Cross hanging in the corporate showroom.

The Chinese parent company is a private enterprise — though the U.S. government has insisted otherwise — but their displays inside the Phnom Penh showroom indicate the company is attempting to associate its project with the Belt and Road Initiative.

A reporter attempted to visit both ZhengHeng and Coastal City’s offices in Phnom Penh to ask about the two companies’ relationship, as well as apparent scam business operating inside the compound. ZhengHeng staff asked reporters to send an email with questions, which went unanswered, and a WeChat contact supplied by Coastal City stopped replying to messages.

However, a ZhengHeng representative reached out to the fraud victim advocacy group Global Anti-Scam Organization to threaten legal action after they posted details of the case and the company’s business structure.

The anti-scam organization also identified Sonny’s friend as Chen Meiyue, who worked as a “drinks server” to a Chinese employer in Cambodia. The organization also claimed that they knew of a second trafficking victim who was recruited by a “close associate” of Chen, but the connection was unclear to reporters.

Two days after his rescue, a representative of Global Anti-Scam tried to lecture Sonny about his friend, warning him in a stern voice not to trust her.

After the warnings, Sonny told a reporter that they were close in university, and he still considered her a friend. Though Alex thought otherwise, Sonny still believed that Chen never received money from Sonny’s sale to the Dara Sakor-based company. He said he still considered her a friend in the end, and doesn’t think she has a job at the moment.

“I believed her because she was working in the buildings and she recruited other classmates to get into the buildings, and the other classmates successfully made money without any danger,” he said.