BANGKOK — As the sky was falling dark, Sitanan Satsaksit took stage in front of dozens of protesters occupying one of Bangkok’s busiest intersections. The protesters were continuing their bid to oust the government of General Prayut Chan-ocha, defying tight restrictions imposed as Covid-19 infections soared.

“This is my first time on stage,” she began her speech on September 5, viewed later by VOD. “I wanted to share something, but let’s not call this a speech because I really don’t know how to make one.”

Addressing the crowd, she demanded justice for her brother Wanchalearm Satsaksit, who was allegedly abducted from his residence in Phnom Penh over a year ago, and other missing Thai dissidents alike. Then she went further, calling out recent police brutality and lambasting the government’s mismanagement of insurgencies in the deep south region.

She wrapped up in less than 10 minutes then left the stage. The rally concluded a few hours afterward without any violence.

A month later, Sitanan learned from other activists that she was being accused of violating a Covid-induced emergency decree for participating in the protest — the first time she ever faced potential prosecution for her activism following Wanchalearm’s disappearance in Phnom Penh.

Sitanan said she might have become a target for her claims about law enforcement neglecting responsibilities and instead oppressing the outspoken. But her lawyer Pornpen Khongkachonkiet believes she was slapped with the allegation for merely making an appearance at an anti-government rally.

“I think [being on the stage] was the trigger, because they didn’t make a complaint over anything she said, just that she violated the emergency decree,” Pornpen told VOD over the phone.

Though it’s a first for Sitanan, criminal prosecution has become a routine reality for hundreds of Thais taking a stand in the country’s recent pro-democracy movement. Fewer have attended rallies in recent months due to a surge in coronavirus cases and violent crackdowns. And authorities have stifled dissent further through a string of charges and slow-moving judicial processes, which critics slammed as a violation of freedom of expression under the guise of disease control.

Sitanan believed it was just another attempt by police to stop dissenters from speaking their minds, but this wouldn’t be enough to stop her.

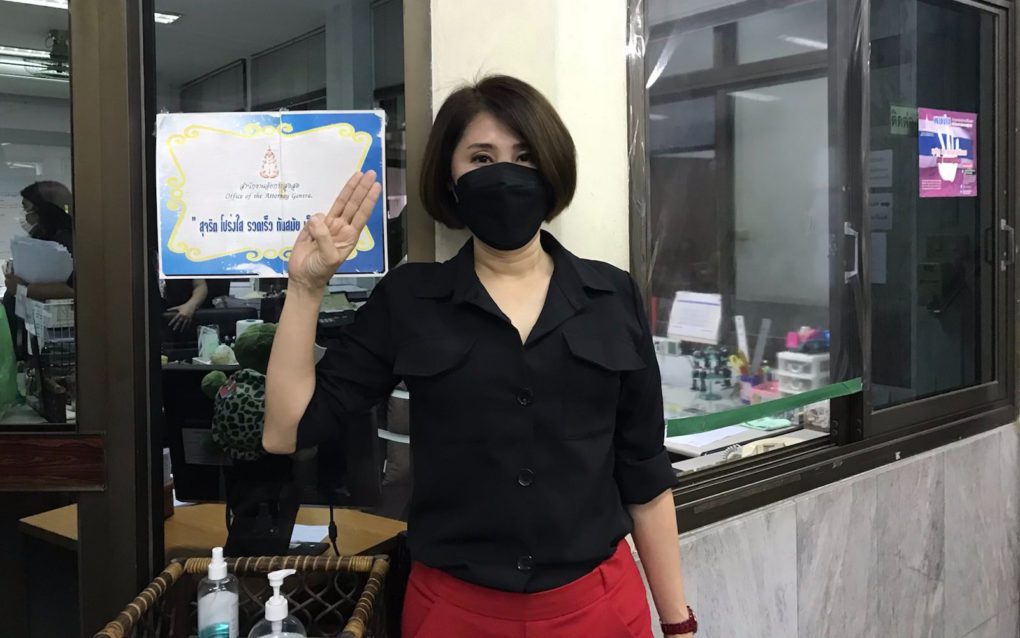

“If they invite me to speak again, I’d go, because I believe I’ve done nothing wrong,” she said on Monday after being called into the prosecutor’s office.

‘Peace and Order’

Since July 2020, Thai police have opened 794 cases related to protests against at least 1,458 people, of which at least 223 are under 18, according to data through September from legal coalition Thai Lawyers for Human Rights. The most common charge is violating the emergency decree — the nation’s Covid-19 response law, which among its provisions bans gatherings and suppresses news and media that officials deem false in the name of national security.

Similar to Cambodia’s own controversial Covid-19 Law, critics in Thailand say their emergency decree has not been used for disease control but rather for silencing protesters who demand a new leader, new constitution and broad reform of the country’s most revered institution — the monarchy.

Yaowalak Anuphan, a lawyer with TLHR, said the enforcement of the law against demonstrators has been so disproportionate that it’s clearly a tool of suppression.

“They enforce the law illegitimately. They can even issue a new law using the power from the emergency decree,” she said. “They said they need it to curb Covid-19. They don’t actually use it for disease control. They use it to control the people.”

On Monday, prosecutors accepted the police’s case file against Sitanan and 11 other protesters for organizing or participating in the September 5 rally in violation of the decree, saying they would decide whether to indict the activists on November 1. Prosecutors would not come out of their offices to give a comment to reporters.

Those who were charged alongside Sitanan for “participating in an unauthorized gathering or activity that risks spreading a disease” were either the rally’s organizers or speakers, including a 16-year-old and performers who sang on the rally stage.

Yaowalak called the charges a new police tactic for suppressing political dissent: “They can’t use deadly force like in the old time.”

In 2010, at least 99 people were killed and thousands injured following the violent breakup of pro-democracy rallies, locking the country’s capital in monthslong conflict.

Though there’s only one recorded fatality since the protest wave began in late 2020 — when an officer had a heart attack while on duty — law enforcement have deployed water cannons, chemical-laced water, tear gas and rubber bullets at these youth-led democracy rallies, resulting in multiple injuries. Riot police have been recorded beating up unarmed protesters, and one leading protester was permanently blinded in one eye after being hit by a tear gas canister.

Although many international human rights organizations — including the UN’s human rights experts — have expressed concerns over Thai authorities’ use of excessive force against peaceful demonstrations, police each time claimed it was reasonable and in line with “international standards.”

More notable is the surge of what Yaowalak called “SLAPP,” or strategic lawsuit against public participation, frequently used for intimidating critics. She said TLHR, which provides legal counsel for these matters, has been inundated with cases rising to about 1,000.

“I think it’s similar to how the Hong Kong police have dealt with [jailed activist] Joshua Wong. Using the judiciary process makes it difficult for other nations to intervene,” she said.

Thailand’s premier Prayut, a military general who has remained in the seat of power since staging the 2014 coup, threatened last November to use “all laws” against the protesters to keep “peace and safety” as political turmoil was escalating. Since then, dissidents were slapped with serious offenses, ranging from emergency decree violations to sedition and the controversial Article 112 — “lese majeste” — which carries a maximum sentence of 15 years in prison.

“The officers need to do whatever it takes in the line of the law to bring peace and order,” said police chief General Suwat Jangyodsuk during a press briefing in August prior to a rally.

Although prominent protest figures more frequently face charges, Yaowalak thinks that police have already stopped differentiating between famous and non-famous protesters. Several reports emerged of protesters being treated harshly after being taken into custody or dismissed of suspects’ rights such as seeing a lawyer, and many contracted Covid-19 while detained.

In response to one Bangkok rally last month, police arrested and detained a homeless Cambodian woman, who was not participating in the protest but was asking for handouts in the area.

Yaowalak said the most obvious irregularity in these case proceedings is the frequent denial of bail requests even though they showed no sign of flight risk. Many protesters still remain in prison awaiting trial, with some held for months.

One of the most outspoken monarchy reform advocates, Parit “Penguin” Chiwarak, holds the most lese majeste counts in Thai political history, according to TLHR, with his 21st charge brought against him earlier this month. Though all cases are still open, his bail requests have been repeatedly rejected, leaving him in jail since August 8. If convicted of all, the 23-year-old faces a maximum jail term of 315 years.

For Sitanan’s case, her lawyer Pornpen also pointed out several anomalies aside from authorities’ failure to serve the activist an official summons. Pornpen felt officials were rushing the investigation, and the accused was denied a request for more witnesses in the inquiry to prove the rally was constitutional and complied with Covid-19 requirements.

Countering Impunity

According to Pornpen, many of the pro-democracy activists also questioned for the September 5 rally have been hit by previous charges, and they offered advice to Sitanan, an advocate for families of enforced disappearance victims who considered herself apolitical before her brother went missing.

Although the lawyer is particularly disappointed by the police’s attempt to prosecute Sitanan, Pornpen thinks it’s an injustice that should not happen to anyone under any circumstances.

“I don’t want the police to make an exception for [Sitanan]. I want everyone to be able to speak freely,” she said. “They threw out charges against a whole group of people, like it’s a policy to cast a wide net. They are abusing their power with no accountability.”

Some protesters and reporters have attempted to use the law to clap back at violent and unjust actions by law enforcement, but legal procedure has proven an uphill battle so far. Of the two lawsuits filed by reporters hit by riot police with rubber bullets, one was dismissed, and while the other was accepted, the court dismissed the plaintiffs’ request to stop police from using rubber bullets and tear gas at protests.

Thailand’s Human Rights Lawyers Alliance last year announced a campaign supporting victims of violence and rights violations by law enforcement, opening 13 countersuits, but cases against the state have been regarded as arduous: The court took 10 years to hold authorities liable for a 2008 crackdown on pro-establishment protesters that led to two deaths and more than 400 injuries, while no one has been held accountable for a 1976 massacre during a peaceful demonstration at Bangkok’s Thammasat University.

Student activist Chayapol Danotai filed a civil suit against police after they issued a warrant against him for allegedly spray painting photos of Thailand’s king even though Chayapol could prove he was outside the province. He told a public forum earlier this month that he was distressed not only by the erroneous warrant filed against him, but also by the police’s lack of remorse after they disrupted his studies and life.

“So did I have to lose sleep, be scared and panicked because I misunderstood? Or actually because you did your job sloppily?” he said in the forum. “What am I in this society? Or what am I in their eyes that makes them feel they could do this to me?”

In the same forum, lawyer Suphamas Kanyaphakpokin encouraged these countersuits, noting that even dismissed cases can raise public awareness and “nudge the justice system.”

“We must shout out to the officers who are bullying the people that we will fight back in every way that the law allows. … It’s not only about upholding the constitution, but also human dignity,” she said.

Shortly before signing documents for the prosecutors investigating her case, Sitanan told VOD that she was already considering legal action against the officers who slapped her with emergency decree charges, even if her case is dismissed or she is found not guilty after going to court.

“I’d like to set a standard that they don’t have the right to bully people, and don’t have the right to press whatever charges to anyone this easily,” she said. “If we do nothing, it would just encourage them and spoil them. They’d think they can do whatever they want.”