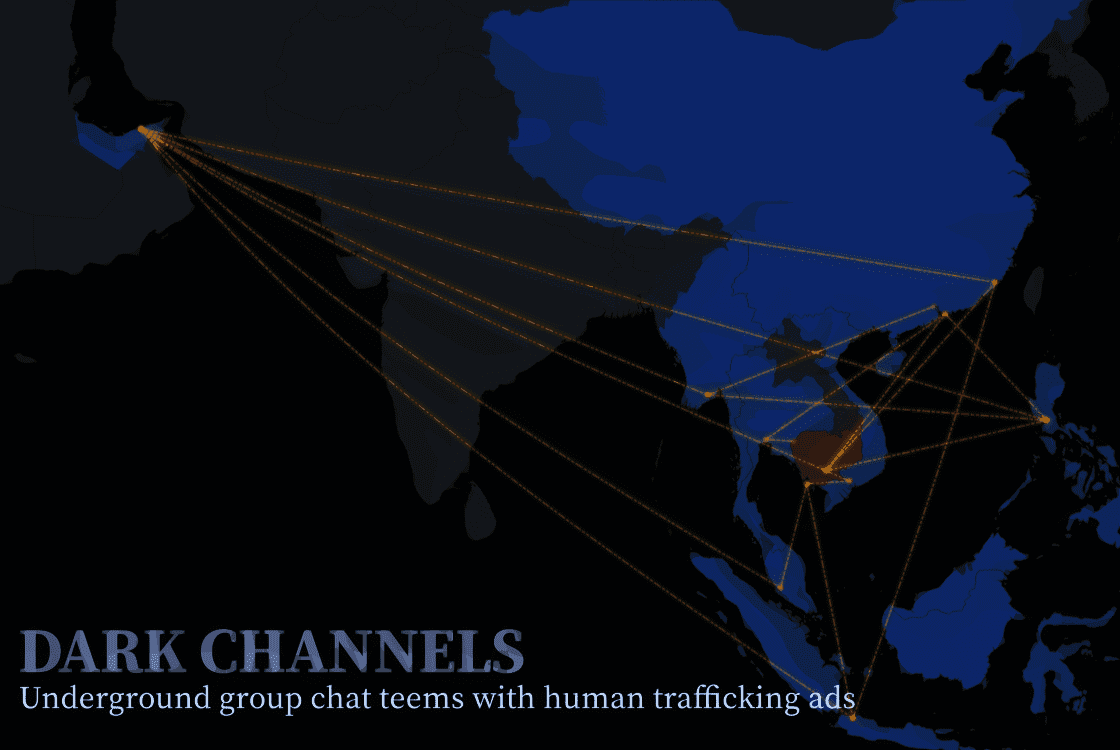

The “White Shark Channel” Telegram group might be open for just about anyone to join, but the work shared within is usually kept strictly in the shadows.

That’s because White Shark appears to be a kind of Chinese-language bulletin for criminal enterprise around the world, a place where organizations in the online scams industry can negotiate human trafficking and illicit commerce in what is essentially plain sight. Each day, posters come to the channel to plug their services or seek those of others — people smugglers, bounty hunters, even scammers looking for new jobs are networking in the White Shark channel.

With more than 5,000 subscribers, the channel was a bustling hub of what seems to be illegal activity. Even still, an anti-scam worker told VOD the channel is just one of what they described as a sprawling world of cybercrime outlets. The digital, open-air black market helps to illustrate how deeply entrenched the scams industry is not only in Cambodia, but in connected locations across the globe.

“I’m easily looking at hundreds of them but personally I haven’t counted,” said a representative of the Singapore-based Global Anti-Scam Organization, who declined to be named due to their ongoing investigations.

The group advocates for victims of “pig-butchering” scams, in which victims are gradually ‘fattened up’ by a fraudster for growing sums of money.

The representative said they monitor group chats on Telegram that cover a broad range of criminal activities. Most of these channels require invite links and are not generally known to scam trafficking victims until they’ve become more savvy in the workings of the industry.

“We’ll join every group chat that we can,” they said. “One of them is for laundering, getting cash around, and another one is for IT. … They even have a telegram group chat where scammers can buy fake profiles, even [fake] sim cards, there are lots of group chats available for many kinds of scams.”

VOD followed the White Shark channel’s activity over the past month to reference it with previous investigations of the scam industry. The posts opened a window into some of the inner workings of the business of scamming, with the darker aspects demonstrated with graphic images and videos of torture, abuse and what looked to be revenge porn.

At one point, reporters received at least 65 job offers within an hour of posting an ad from a fictitious young Chinese man seeking work in the Cambodian scam industry. The made-up job seeker was an ideal candidate for online fraud businesses — experienced, in possession of his own passport, and not expected to pay a ransom to any previous scam employers to move on to another job.

The job offers ran the gamut of those typically seen in the industry, with offers flowing in all over Cambodia from a list of facilities made notorious for their links to fraud and cybercrime. The jobs themselves would have been anything from working at click farm-based scams to pig butchering cryptocurrency sales targeting Chinese nationals and others around the world.

Other gigs would have had the hypothetical job-seeker promoting adult streaming channels, esports platforms, online gambling and betting of all sorts, but especially related to the upcoming football World Cup.

VOD also conducted a more methodical analysis of about 353 other posts made to the White Shark channel over a period of six days. These revealed a labor market teeming with employers and would-be employees looking to connect. It also helped to show the global scale of the industry — while recent media and civil society investigations have shown Cambodia to present a relatively open market for scammers with connections to political and social elites, the country is just one hub where the globalized industry has taken root.

| Workers for Sale | |

|---|---|

| Dubai | 28 ads |

| Philippines | 27 ads |

| Cambodia | 24 ads |

| Myanmar | 10 ads |

| China | 3 ads |

| Thailand | 2 ads |

| Indonesia | 1 ad |

| Malaysia | 1 ad |

| Vietnam | 1 ad |

| No location | 28 ads |

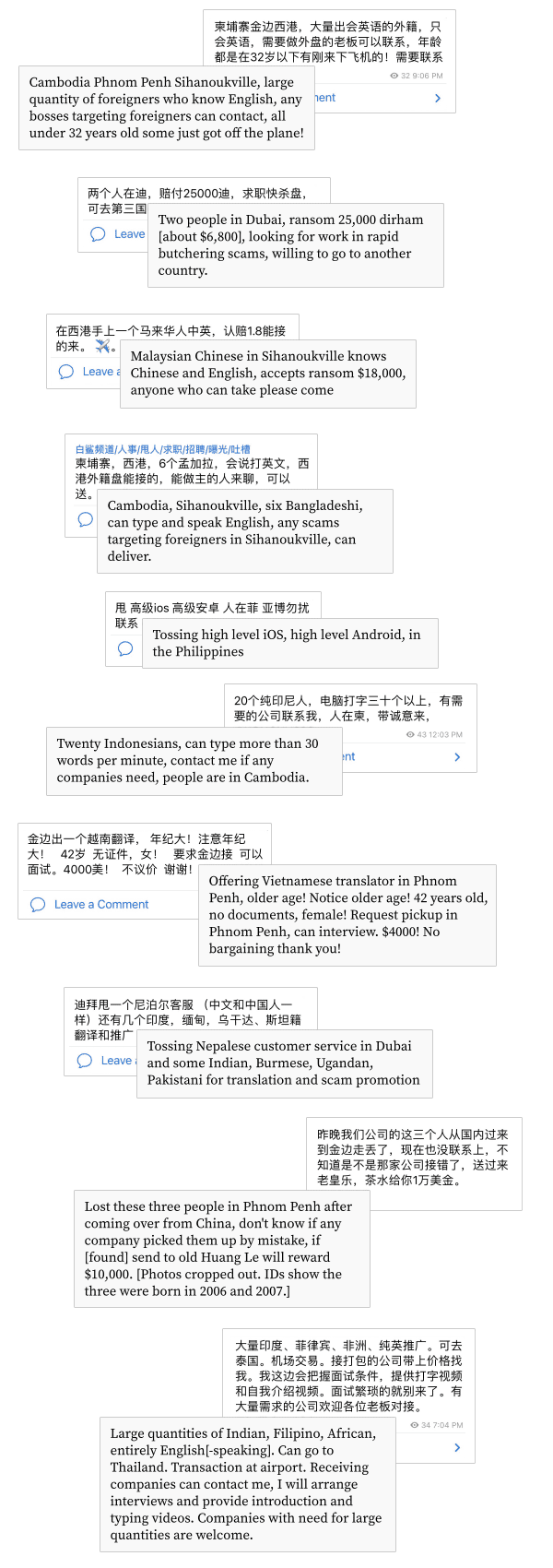

The analysis of posts found 125 advertising what appeared to be trafficked people for sale, some for prices as low as about $2,000. At the same time, it was unclear to what extent some of these people had willingly agreed — or even actively sought — to be smuggled across borders to find work for scam organizations, which describe themselves using various slang terms to refer to illicit activities.

Of the total 125 human trafficking ads, 24 were clearly mentioned as being in Cambodia. Dubai and the Philippines accounted for 28 and 27, respectively, while 10 more were in Myanmar.

Twenty-eight ads did not mention any locations.

Jeremy Douglas, the regional head of the U.N. Office of Drugs and Crime, said his office has also been tracking “several” channels linked with suspected scam operations around Southeast Asia, namely in “Special Region 1 and Special Region 4 of Myanmar, Bokeo in Laos, in the Philippines, and in different places in Cambodia.”

Bokeo province in Laos is home to the Kings Roman Casino in the Golden Triangle Special Economic Zone, a site made infamous by alleged involvement in numerous criminal enterprises.

The Telegram channels monitored by UNODC mainly target Chinese-speaking employees and potential trafficking victims, Douglas said, and are not as openly illicit as White Shark.

“Unlike White Shark HR which seems to be explicitly trading laborers and trafficking victims, most appear to be recruiting pages used to lure Chinese-speaking labour — the pretense of legitimate recruitment makes it difficult for law enforcement to intervene,” he wrote in an email.

From the Global Anti-Scam Organization, the representative said that trafficking victims often struggled to produce concrete evidence that they had been tricked to come over, and trails of communications were littered with fake identity.

“That’s a huge problem for things that fall under the umbrella of cybercrime,” they said, adding that such gray areas made it difficult to call out the organizations involved and the connections between them.

Most of the people being advertised for sale during the six-day analysis period appeared to be Thai, which was represented more than any other nationality among the several nationalities available for purchase. However, other weeks showed very different demographic patterns, with few Thais and many more Vietnamese or Chinese people being sold in either Dubai or the Philippines.

The phrasing used in these posts is vague, often with little identifying detail. Advertisers will simply mention they have people, maybe specifying their nationality, language skills, whether they can type well or have prior experience with scamming.

Advertisers contacted by VOD under the pretense of seeking more information about purchasing trafficked people seemed to have no problem quickly offloading — or in their words, “tossing” — the ones they had listed.

“Tossing two Vietnamese, currently people are in Moc Bai, two women, no problems typing, anybody who needs come quickly,” one poster wrote.

Though Moc Bai is officially in Vietnam, across the border from the Cambodian city of Bavet, Chinese-language social media users commonly use the Vietnamese name to refer to Bavet itself.

When contacted by VOD, the poster said the women had already been claimed.

“All taken, if I have any more I will let you know. If you have anyone to toss you can also contact me, we can take care of each other,” the poster said. “Keep in touch, we can mutually benefit each other.”

Later on, a different poster sent VOD a location where a prospective buyer could interview a man being sold.

“In Sihanoukville, tossing an Indian, can type English, good price, direct message if can take,” the poster’s initial advertisement read on the White Shark channel.

The poster told VOD the man could be had for $2,500 and was a “beginner” in terms of his work experience. They sent over a picture of his passport, which showed the man was actually from Bangladesh and born in 1994.

The poster said they and the man were at a place called the Xing Yue Tai Hotel and sent a location near the Jin Bei 1 casino and Golden Lions roundabout in Sihanoukville. When the supposed buyer arrived, the poster said, they would take the man down to the lobby for a chat.

Douglas of the UNODC said that some scam operations appear to be “masking themselves behind, or operating alongside, supposed online casino operations.”

“Cambodia is a significant player, and it is really no surprise given it has had significant physical and IT infrastructure in-place for gambling operations, and the casino industry took a hit following the ban on issuing new online licenses — revenues were needed and it was a pretty simple pivot,” he wrote.

Speaking to the scam industry in Cambodia and in its neighbors, Douglas also pointed to factors such as weak governance and access to Chinese-speaking labor in special economic zones as helping to drive the switch, but continually emphasized the role of casinos and online gambling.

“We can’t say definitively who is behind it all, but some significant casino operations are connected. Notorious hubs like the KB Hotel are heavily involved in the Sihanoukville casino scene with at least 5 casinos, and in Special Region 1 and Myawaddy in Myanmar,” he added.

Back in the White Shark channel, the rest of the content analyzed by VOD included a mix of subjects. Reporters saw 94 posts about job-hunters looking for better postings at competing scam organizations, and 92 from people who sought to leave bad reviews for smugglers, traffickers and other shady businesses they felt had not fulfilled agreements.

The group’s full name is “White Shark Channel/HR/Tossing people/Job hunting/Hiring/Exposure/Complaints.”

Among the job-hunters were people from several different countries including China, Vietnam, Indonesia, Malaysia and Russia. Some posters, particularly those in China, were looking to stay in their own country and find remote work, advertising skills such as hacking and website engineering. About 5% of the job hunters said they were looking for more ‘normal’ work such as being a private chef, accountant or business administrator.

There were also 31 posts advertising bounties for people, offering rewards either for their apprehension or useful information about their whereabouts. Some of these posts offered little detail about the targets other than their name and basic description, while others included information about why the poster wanted them.

One man, a post read, had worked as a courier but had stolen a parcel of illegal drugs from his employer, who was now trying to hunt him down. Other employers put out bounties for scam laborers who ran away from the facilities where they had been held and forced to work.

Some of the posts reviewed outside of the analysis included screenshots of messaging conversations between employers and their employees who had fled.

These kinds of posts, which were usually made by the employers, usually included captions criticizing the workers for what the posters deemed ungrateful behavior — especially in cases where scam organizations had helped to smuggle people out of China for work.

The remaining posts analyzed by VOD included five with media articles about criminal cases in Southeast Asia, two looking for smugglers for hire and two more seeking information about missing family members.

There was also one from a poster who said they “can constantly supply Thai [people]” and were seeking an experienced scammer to help them set up a business.

The final post was from a pimp, who for three days posted ads featuring scantily clad women.

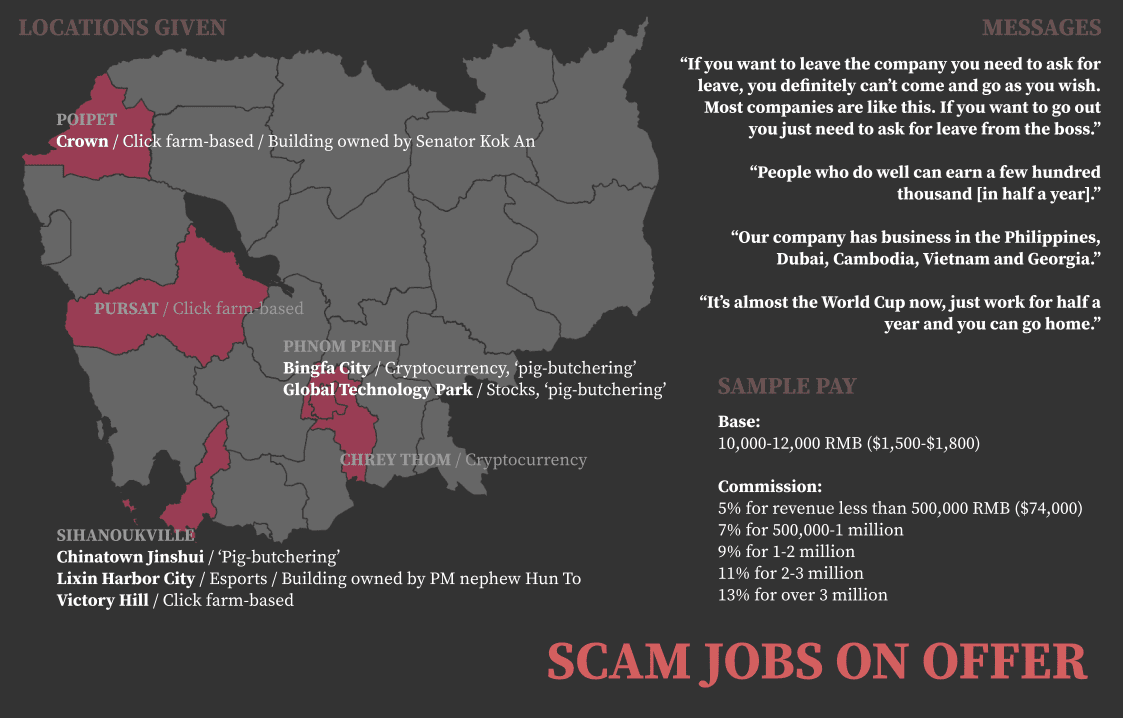

But while many posts made in the channel were light on details, the flood of offers from Cambodian operators to the fake job-seeking ad were much more forthright. Those offers came in from operators in Phnom Penh, Sihanoukville, Bavet, Poipet, Pursat and Chrey Thom.

They typically began by seeking some basic personal information from the supposed applicant, such as their location, what kind of position they wanted and if they had possession of their passport. One job was 12 hours per day starting at 11 a.m, and offered two to four days off per month.

Base salaries ranged from about $890 to $1,486 per month for a scammer, and $1,800 for a team leader. Workers also are promised that they would earn a commission within their work groups, which often tend to focus on running scams as a team. The more the group earned as a unit, the recruiters told VOD, the higher their commission as a team.

The commission can be a cut of the revenue, though sometimes they are in kind: one scam based on cryptocurrency wallet theft advertised rising rewards of a Gucci leather belt, iPhone 13 Pro Max, Cartier ring, Rolex watch, BMW 3 series and Porsche Cayenne.

Many offers also had a minimum performance requirement: If a worker cannot reach it, they can be “eliminated” from the company — possibly how people end up being sold on to other operations.

At least some of the posts in the channel contained warnings of the industry’s darkest impulses. These include often-graphic videos and photos that appear to show scam laborers being tortured and beaten by their captors, as well as those showing other forms of abuse.

One post, a two-part series taken from WeChat with a video and photo both appearing to show the same man being waterboarded — a kind of torture method that simulates drowning — described the nature of scamming in Cambodia in bleak terms.

The video shows a man restrained in a sitting position by zip ties binding his arms and legs to a chair set on a concrete floor in a large, open room. Another man sits facing him with his back to the camera, hunched forward and holding a lit cigarette. This other man is speaking briefly in a low voice, echoed by a woman who seems to be holding the camera.

The photo seems to show the next development — the first man still bound to the chair, identifiable by the designs on his clothing, but now tipped onto his back against the floor with a towel placed over his face. The man who was sitting earlier with his back to the camera is pouring water from a jug over the towel on the restrained man’s face, suffocating him

A few paragraphs of Chinese-language text shared on the image says the scene happened in Phnom Penh. Another caption on the video lays out the terms of the scam industry as it exists in Cambodia.

“They thought, this is Cambodia, so they can do whatever they want. In reality, it’s sort of true, they have lots of money and can even kill people — even with blood on their hands, they’re not afraid, because here they can use money to fix everything,” the caption said. “If this guy in the video drowned and died, they could just say it was an accident and give the police some small amount of money, and nobody would care about the cause of death, even if there were marks on his limbs showing he’d been tied up or strangled.”

The poster went on to say that local policemen “only see dollars, they don’t see wounds.”

“In the scam business of Cambodia, the life of a human is worth even less than an animal,” the poster went on. “The employees are locked in a vicious circle. … They scam, can’t meet their target, are beaten and tortured, and then sold to the next business, where they start again.”

Numerous civil society groups have beseeched Cambodian authorities to take firmer action to crack down on scam operators, many of whom operate in well-known compounds.

While police do extract laborers from these sites on an ad hoc basis, there have yet to be any clear penalties for their managers. Recent media investigations have found links between the compounds and various Cambodian elites.

Interior Ministry spokesman Khieu Sopheak claimed it was impossible that police would not investigate a suspicious death.

“Any citizen who has died unnaturally, there is always an investigation and police conduct an autopsy,” Sopheak said. “Their family would not stay silent if such a thing happened. Why would they understand more than their family? This is a very crazy and blind person. Our authorities are not blinded like them and they are the one who is blinded.”

“It is not possible that when people die, we would throw them away like a ghost dog. When any person dies, there is an official to check and investigate.”

He said that torture did not exist, and offered that all countries had problems.

“There is no country that is perfect or heaven, and even superpower countries have bad things.”

*Chinese-speaking reporters contributed to this article, but are not named due to safety concerns.