LAKE SAGAMI, Japan — Since his early school days, Kenji Kuraki remembers being shunned by his classmates, called names and even discriminated against by a teacher. The bullying was the result of prejudice against him and his identity, he says.

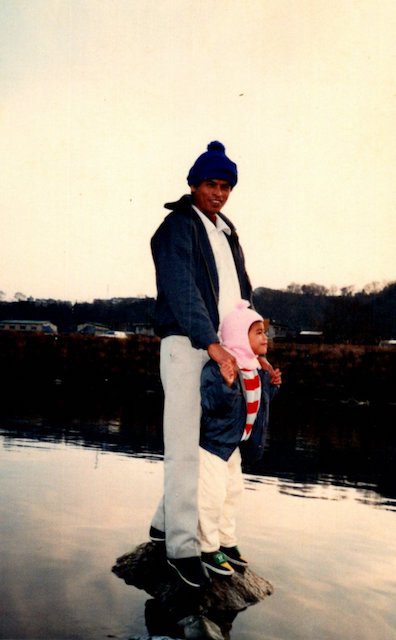

Kuraki was born Roeum Reth in 1982 at the Khao-I-Dang Holding Center, a Cambodian refugee camp in Thailand. He immigrated to Japan with his parents when he was 4 years old. By the age of 5, his left leg was paralyzed by the poliovirus, he says.

As an immigrant and person living with a physical impairment in Japanese society, Kuraki says it was like having a “double disability.”

“My classmates made fun of me because I am the son of Cambodian refugees,” he says. “I wanted to fight back but I couldn’t catch those bullies when they ran away.”

But as a teenager growing up in Aikawa, about a two-hour drive from central Tokyo, Kuraki found an activity that helped shape him and his future: rowing. It even led him to become a Japanese citizen.

Kuraki, 38, is a former para-rower on Japan’s national team. Today, he coaches younger rowers living with cognitive disabilities and encourages them to pursue their dreams, like he did, regardless of the hardships in their way.

His passion for the sport helped him overcome feelings of alienation in his adopted home, and eventually led him to win a gold medal during the All Japan Masters Regatta in 2016.

“I always feel confident whenever I am rowing on the water,” Kuraki says, grinning while his team trains on Lake Sagami in February. “Maybe because I forget about my left leg while rowing the boat.”

Memories of Mix Tapes

Kuraki’s parents fled Cambodia after the overthrow of the Khmer Rouge regime in 1979. They and their son were among approximately 1.3 million refugees displaced by the Indochina wars who resettled in countries such as Japan, the U.S., Australia and Canada from the late 1970s to mid-1990s, according to Japan’s Refugee Assistance Headquarters.

The Japanese government accepted more than 11,000 refugees from Cambodia, Vietnam and Laos up until 2005, including 1,357 Cambodians, a tiny portion of Japan’s population of 126 million.

Kuraki says he learned about Cambodian history as an adult and barely speaks Khmer but fragments of his childhood memories of Cambodia resurfaced when he watched the film The Killing Fields. He said he can still recall images of dead bodies left outside the Thai refugee camp where he was born near Poipet.

He also remembers the music recorded onto cassette tapes that his parents used to play at home in Japan, which started with the sound of jet engines and then dissolved into a Khmer-language duet.

“My parents enjoyed listening to Khmer mix tapes as the songs encouraged and lifted their spirits,” he says in fluent Japanese. “It still resonates in my head.”

“But I still don’t know the exact meaning of the songs because I don’t understand Khmer that well,” he admits.

Kuraki says his life would have been more difficult if his parents had stayed in Cambodia, but he still hopes to give back to their homeland someday.

“I would have had a harder life because of my paralyzed leg,” he says. “Now, I am happy with my family here [in Japan], but I would like to contribute something to Cambodia too.”

Still, his childhood in Japan was not easy.

When he was in elementary school, Kuraki was accused of hitting a female classmate. He denied the accusation, but his teacher didn’t believe him and made him stand still while interrogating him for what he says felt like hours. Eventually, Kuraki says he accepted the blame, even though he didn’t hit the girl, because his left leg was in serious pain.

Kuraki recalls what his teacher had told him: “You always lie because you are a foreigner.”

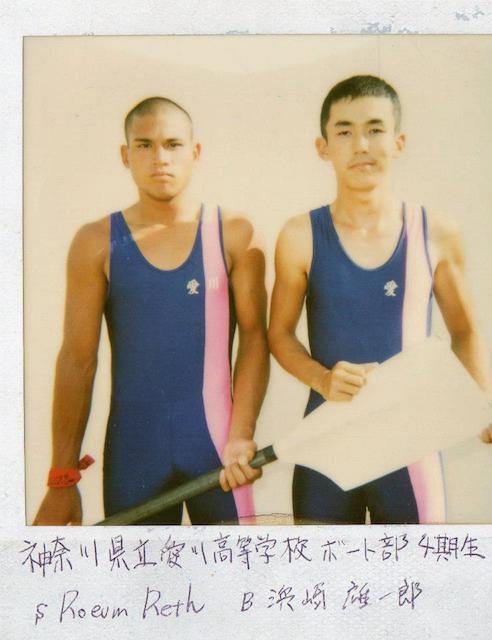

Then, at 15, he joined his high school’s rowing club. It became more than just an after-school activity for Kuraki.

While other sports clubs didn’t accept him as a full-fledged member of the team due to his disability, in the rowing club he was able to compete against anyone. Overtime he strengthened his skills enough to compete in national-level regattas against students without disabilities.

Pulling oars in sync with other rowers helped Kuraki overcome the bullying he experienced and gain self-confidence.

“Never give up on your dream. That’s what I learned from rowing,” he says.

Seeking a Nation to Represent

When the International Paralympic Committee announced that para-rowing would make its debut in the 2008 Games in Beijing, Kuraki was a young man.

He was determined to compete in the games, but his lack of citizenship later proved to be a new obstacle. Hoping he could represent Cambodia, Kuraki visited the Cambodian Embassy in Tokyo to request help becoming a citizen of his parents’ country, which he has never visited, even now.

“I wanted to become a Cambodian national athlete to compete in international competitions,” he recalls. “At the age of 25, I was told by a high-ranking official that the embassy can’t help me because my parents are Cambodian refugees.”

Kuraki’s wife Miho says she was outside the embassy, expecting that her husband and his father, Roeun Roeum, would come back with good news.

“He was devastated. I couldn’t find words to say to him,” Miho says of Kuraki.

Disheartened but determined to compete, Kuraki decided to become a naturalized Japanese citizen while he trained alone or with his old schoolmates. In 2013, he became a Japanese citizen. Three years later, he joined Japan’s national para-rowing team.

But by the time the Rio Paralympic Games were held in 2016, Kuraki was already 34 and the team failed to qualify. He decided to retire from competition in early 2018 as the condition of his left leg worsened.

After his retirement from rowing, he formed a private team for people with disabilities.

“I want to make an environment where people embrace diversity and anybody can thrive,” he says of his team of about 30 rowers.

Jun Castro, who rows on Kuraki’s team, says Kuraki is a good coach who understands the feelings of marginalized people. “Mr. Kuraki looks intimidating but his heart is very warm,” Castro says, describing his coach’s intense glare.

Earlier this year, six other rowers from Kuraki’s team were training for competition in the 2020 Paralympic Games in Tokyo, which were scheduled to begin in August.

But last week, with the number of Covid-19 infections continuing to rise amid the global pandemic, Japan and the international committees for the Olympics and Paralympics announced that the Tokyo 2020 Games would be postponed until next year.

Following the decision to delay the Games, the re-selection process and who will qualify to compete remain uncertain. Kuraki says he wants his rowers to stay positive and push forward toward their goals, like he has.

“It must be heartbreaking for them but they have to condition themselves mentally and physically for next year,” the coach says.

Before the Tokyo Games were postponed, Kuraki had already set a personal goal outside the world of rowing: to better understand his Cambodian roots and share them with his three children.

“I want to go to Cambodia with my kids and tell them, this is daddy’s country.”

Correction on April 7, 2020: The article originally misstated Kenji Kuraki’s age at the time when the International Paralympic Committee announced that para-rowing would make its debut in the 2008 Games in Beijing.