Some parts of Phnom Penh have become increasingly digital over recent years. Nowadays, you can easily order your food online or book your tuk-tuk with an app any time of the day. At first sight, Phnom Penh looks smarter than it was five years ago. But to become a real smart city, Phnom Penh needs its citizens’ participation in urban planning.

As the world population is constantly growing, more than ever moving to urban areas to find better accessibility and employment options. The growing urban population will consequently lead to further demographic and economic expansion. Aside from environmental impacts, it will particularly pressure modern cities’ urban spaces and administrations. Common challenges such as resource management, congestion, waste management and environmental protection are stressing the future of cities.

To tackle these challenges, the so-called “Smart City Concept” was established. It focuses on innovation in city management, its services, and infrastructure, by finding smart solutions to urban problems. A smart city enables its citizens to be an active part in the solution finding, by encouraging their participation, especially through the usage of information and communication technology.

While there is no consensus on a broad definition of a smart city, the following definition from Asean can be used as an example: “A Smart City is a well-performing city built on the ‘smart’ combination of endowments and activities of self-decisive, independent, and aware citizens.” It is inevitable that a Smart City only earns its status of “smart” due to its citizens actively participating and contributing to the development of the city.

Asean Smart City Network

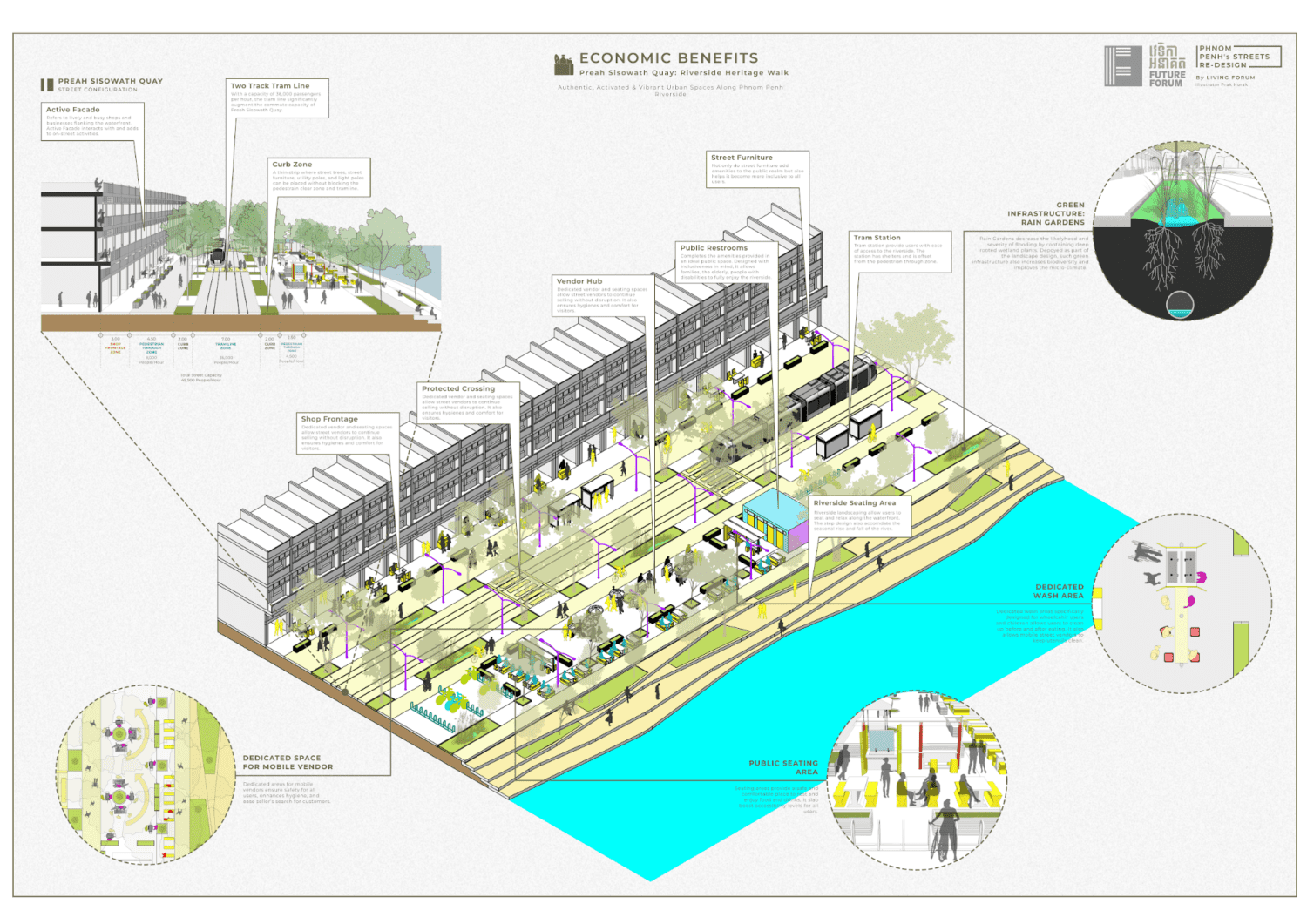

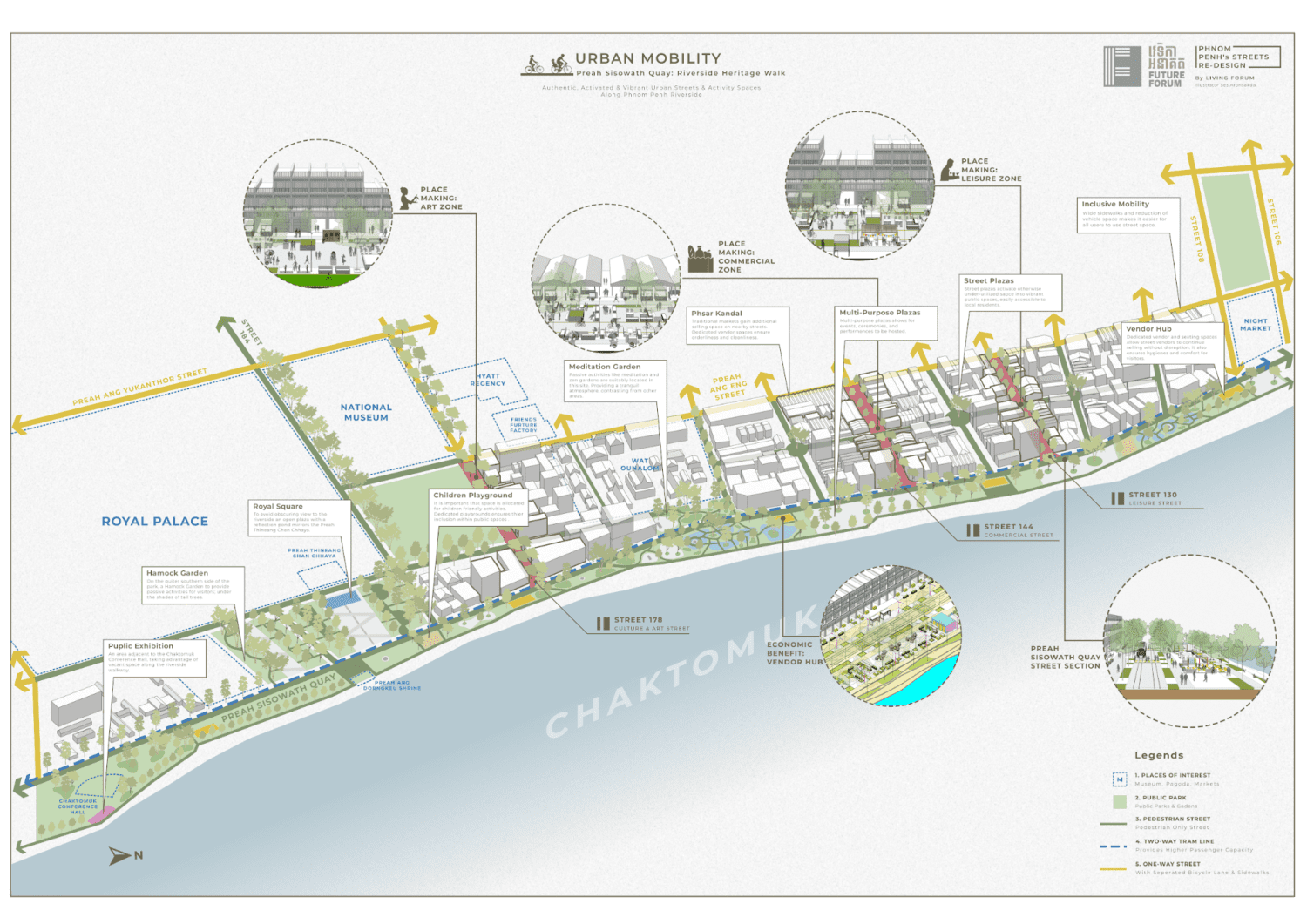

In 2018, Cambodia became a participant in the Asean Smart City Network, in which three Cambodian cities, namely Battambang, Siem Reap and Phnom Penh, are taking part. The network aims to provide a higher quality of life to its citizens by improving urban life on a social, economic and sustainable scale. The plan differs among the 26 participating cities, and Phnom Penh focuses only on the three key areas: efficient and green infrastructure, a healthy urban environment and economic growth, and civic engagement through social media or crowd-funding platforms for improving public space and public transport.

Current projects of Phnom Penh are the 11 Sidewalks Rejuvenation Project and the improved efficiency of Phnom Penh public transportation. Even though civic engagement was initially planned to be included with the help of digital tools, this has yet to be realized. Moreover, it can be questioned how impactful these projects have been on citizens’ lives and if they are ambitious enough to transform Phnom Penh into a smart city. Although these projects could benefit quality of life, the following question should be asked: Are citizens involved in the planning process of the projects, and are they in alignment with their needs?

Digital Citizen Participation

Although the residents of Phnom Penh can elect their commune councils, whose numbers consequently affect the city council for a legislature period of five years, Phnom Penh’s board of governors relies on nominations from the Interior Ministry. Therefore, the opportunities for the citizens to elect their favored and most suitable representatives are limited, as is their direct influence on city planning.

While only relatively few approaches to include citizens have been implemented, a pilot project “Implementation of Social Accountability Framework Phase II” in Sen Sok district was established as a model for promoting citizens’ participation in Phnom Penh. The four-year project (2019-2023) aims to empower citizens to talk with authorities on budget procedures and service improvements.

Data on the service quality is collected via “scorecards” from citizens, which are used to build action plans. The project claims to also support local NGOs and share information about ongoing projects by using digital platforms. It says it aims to reach disadvantaged groups.

However, a reflection workshop on the ongoing project — organized by Oxfam and the Advocacy and Policy Institute — concluded that participation in Sen Sok was limited due to a lack of information and difficulties in identifying target groups.

When choices are mostly determined from above, they are likely to dismiss people’s needs. City council elections, for example, would give residents a choice in who will tackle the issues that are important to them. This can consequently lead to smarter planning processes and might also lead to a more engaged society, in which voices and opinions are heard.

What a Smart City Could Be

While domestic and foreign investment in real estate has resulted in economic growth, they also brought several challenges and downsides for Phnom Penh. Especially in terms of urban planning, it led to an uncontrolled construction boom, in which citizens’ needs beyond economic development were placed second or not even considered. New “development” projects have led to the displacement of numerous families from their homes and forced them into new living conditions, sometimes without compensation.

As decision-making remains highly hierarchical, many public projects don’t necessarily align with people’s actual demands. To change that, they must have a vote on ongoing projects and the administrations must be responsible for providing access to engage.

The example of the pilot project in Sen Sok, despite its challenges, can be expanded across Phnom Penh. With it, the city could decentralize urban planning and overcome the challenges and concerns of residents by closely working with them. But to do this, an accessible way of including every citizen must be found.

The smart city concept with its citizen-centered approach can be seen as a great and easy-to-establish opportunity for Phnom Penh to face its urban challenges. But besides only theoretical approaches, the city must actively contribute to that concept. Therefore, to become a smart city, it needs to be as easy for its citizens to be engaged in city planning as to book a tuk-tuk online.

Lino Arian von Appen is an undergraduate student of Social Science with a specialization in Intercultural Relations at the University of Applied Science Fulda. He was a former research associate at the Konrad-Adenauer Foundation’s office in Phnom Penh, Cambodia.