Tay Ngerb walks down a grassy hill, heading straight for a bamboo shrub. After walking 10 meters through the thicket, Ngerb points to a concrete grave littered with bamboo leaves. Two people immediately start brushing off the dead leaves, and an elderly lady — the deceased’s wife — cracks open a can of soursop juice and places it with other offerings.

Ngerb takes water from a peang, a dull ochre traditional Bunong jar that has been left beside the grave, and pours it on the concrete. He repeats this a few more times. He explains that the peang is used to store items — like farm tools and personal items — and, more importantly, demarcates the location of the graves, most of which are unmarked.

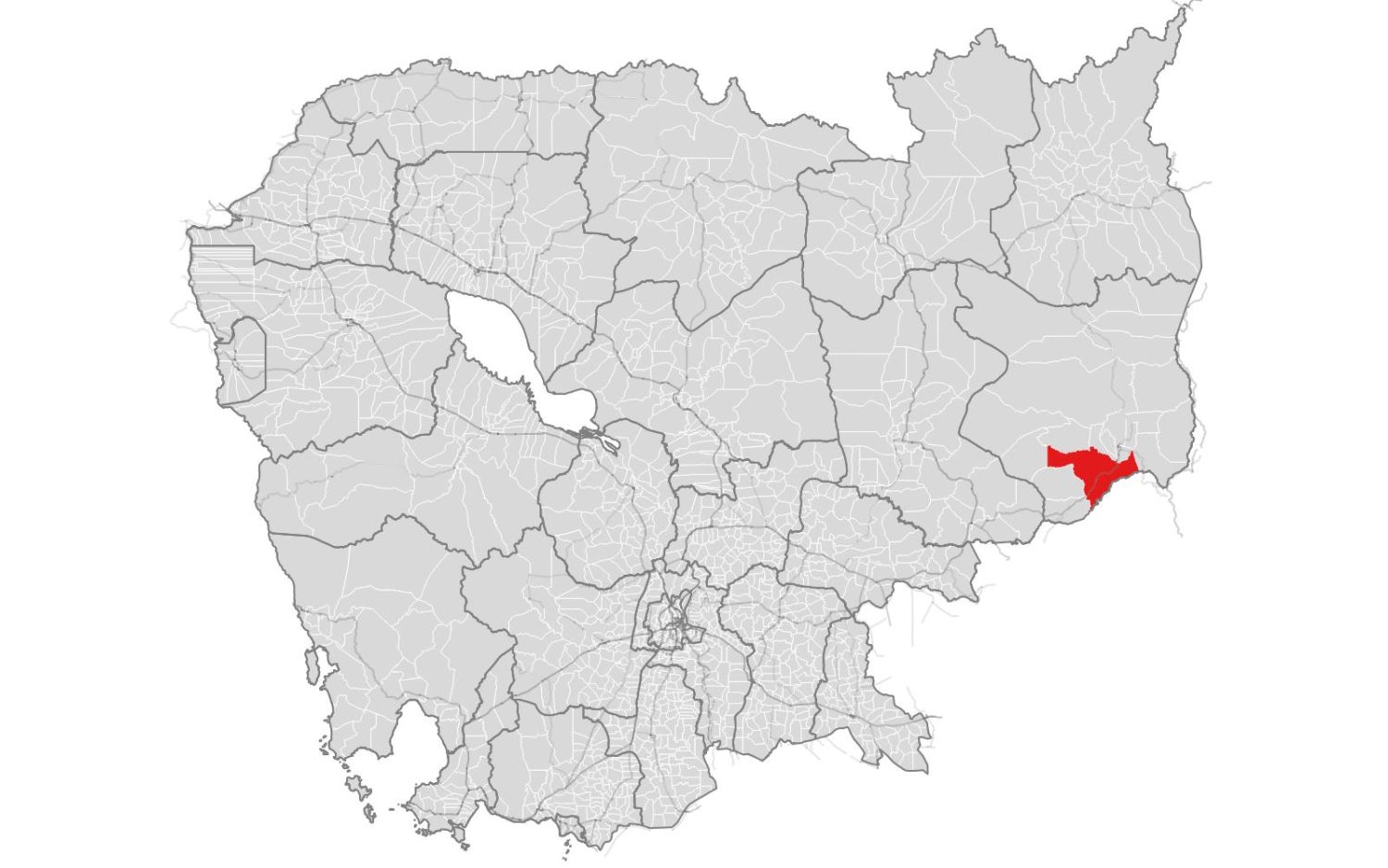

But in late 2018, the indigenous community noticed missing peang. It first started with fence posts coming up on the 30-hectare hillside land in Mondulkiri’s Sen Monorom commune, in O’Reang district. Then the peang started disappearing, leaving graves unmarked.

“They wanted to eliminate the evidence that we buried the dead there,” Ngerb said.

The missing peang posed a precarious dilemma for the residents — how would they locate their ancestors’ graves. “We dare not dig to find the graves,” he said.

The young man said village residents had met with commune officials and asked for help, but all the commune chief and councilors would do for them was suggest they accept compensation for the land.

He was perplexed by the councilors’ suggestion. Ngerb said they have never been approached by a broker or the supposed landowner offering money.

“We said we didn’t want to accept the money at the meeting, because this land is not private land, nor does it belong to any one individual,” Ngerb said.

“If you accepted, you would be guilty because this is the land for the common interest.”

The Sen Monorom Bunong community’s experience is far from one-off. Mondulkiri is riddled with land disputes and land sales propagated by land speculators and development projects, including a proposed airport in the province.

This lust for land had the complicity of local and national politicians. An Interior Ministry investigation from 2020 named 10 individuals — including a senator, district governors and commune chiefs — as being involved in illegal land sales or grabs. The investigation and release of the report was a rarity in a country where land disputes run rampant, often with little acknowledgement of wrongdoing by the government.

Tay Blong is the nephew of the man — a former Pu Rang village chief — buried at the Sen Monorom traditional gravesite. He is also the chief candidate for the Cambodia Indigenous People’s Democracy Party in Sen Monorom commune.

Blong is hesitant to identify who is responsible for the land sale, only placing blame with the commune office for failing to protect the land. “I can’t say their names, but I can only tell you that they are the local officials,” Blong said.

He adds that he and some residents had removed the fence posts appearing on the hillside, but were threatened by the alleged owner of the land. They again went to the commune hall.

“We asked [the commune officials] to solve it for us, but they didn’t,” he said. “They asked us to negotiate or keep quiet.”

One of 10

Thvan Trel arrives for an interview with reporters 60 minutes late. Trel is one of the 10 officials implicated by the Interior Ministry in land grabs, and is running again for commune chief at the June 5 election.

The sitting CPP commune chief places two phones and a pink plastic pouch on a wooden table at the commune hall. She then proceeds to make a 45-minute defense of her tenure as commune chief.

The commune chief is also Bunong, and grew up in the area until her family moved north to Koh Nhek district, fleeing American bombing in the 1970s. She was first elected in 2012 and is in her second term heading the commune council.

She admitted that the commune, and district at large, had seen its fair share of land disputes. She listed small land disputes between villagers and private companies or individuals and the proposed Mondulkiri airport site.

But she admitted to no wrongdoing on her part, and said she had resolved any dispute that was brought to her attention.

“There were some small land disputes but we solved it peacefully,” she said.

Asked about the Interior Ministry report, Trel immediately evades blame.

“What I heard is that grandfather Noy Sron made a request and we signed it,” she said.

Trel had signed documents presented to her by CPP Senator Noy Sron, transferring around 500 hectares of state land to the politician, she said. She didn’t even put a date on it or use the commune stamp, just her signature.

“He told us he had a request from his superior,” she added.

This was the only time she had signed a document under pressure from a senior official, Trel said. The commune chief said she was punished for the incident — Trel did not elaborate on the punishment except to say she was warned not to sign documents without closely reading them.

While Trel and two other commune chiefs were given minor penalties, Sron was let off with an apology. The senator enjoys immunity. Of the 10 people implicated, only a Koh Nhek district governor was transferred to the Interior Ministry.

“Now, that case has ended,” she said. “The land is transferred back to the Ministry of Environment, and the ministry patrols that land every day.”

She also denied any dispute with Bunong burial grounds in Pu Rang village.

“Regarding the clearing of burial grounds, there is no such case happening here, nephew,” she told a reporter.

Another Dispute

Andoung Kraloeng is a village on the southern extreme of Sen Monorom commune, bordering the Keo Seima protected forest. Even in this village, fingers point at Trel.

“We lost burial land that our ancestors had built; it has affected our traditions,” said Sokha Thot.

Thot is the head of the Bunong community center. He said indigenous people in the village had communal lands they were using as a burial ground and for agriculture. Around four years ago, excavators entered the land, cleared the graves and placed fence posts around the land, he said.

The land had been given to a local oknha to build a resort. Again, village residents asked Trel for help but with no luck.

“She should not stay with the powerful. She serves the people, not the oknha,” Thot said.

Thot said the community was given some compensation for the lost land, but did not provide additional details.

Trel sidestepped the controversy when asked by reporters about the land dispute and only said residents were given money for the land and were using another site for their burial grounds.

With all the land disputes during her term, the commune chief heaves a deep sigh when asked about her chances at the upcoming election.

“Regarding the vote, I don’t know whether I will lose or not. Let’s wait and see the obvious,” she said. “I think people should not get mad at me about this because I’m not in control of it.”

However, residents’ opinion of Trel is far from cheery.

“I don’t know who will win, I think there must be a change,” said Ngerb, standing near his uncle’s grave.

Sitting near the Bunong community center in Andoung Kraloeng village, Thot said, “I think she should quit. But in this generation, the wrongdoer becomes right and the right person becomes wrong.”