New data from an international forest monitoring program shows a slight increase in deforestation in Cambodia last year, with new spots of forest clearing moving deeper into Cambodia’s remaining dense forests.

Cambodia’s protected areas lost 47,639 hectares of tree cover in 2020 — an area larger than the whole Angkor Archaeological Park — according to new data from satellite imagery service Global Forest Watch.

Annual tree cover loss in Cambodia’s protected areas peaked in 2012, with more than 61,100 hectares shed, according to the data, which goes back to 2001. Total forest loss last year increased slightly from the 47,535 hectares lost in 2019, according to the data.

Prey Lang Wildlife Sanctuary consistently experienced the worst levels of forest loss, according to global forest cover satellite imagery data compiled by the U.S.’s University of Maryland. Not only did the biodiversity sanctuary see the highest amount of tree cover loss last year, but it had the most total deforestation of any protected area in the past five years.

Other protected areas — including Kulen Promtep Wildlife Sanctuary in Preah Vihear, Siem Reap and Oddar Meanchey provinces, and Boeng Per Wildlife Sanctuary in Kampong Thom — also lost tens of thousands of hectares of forest in the last five years, but an analysis of the Global Forest Watch data showed a general slowing of the deforestation in those areas.

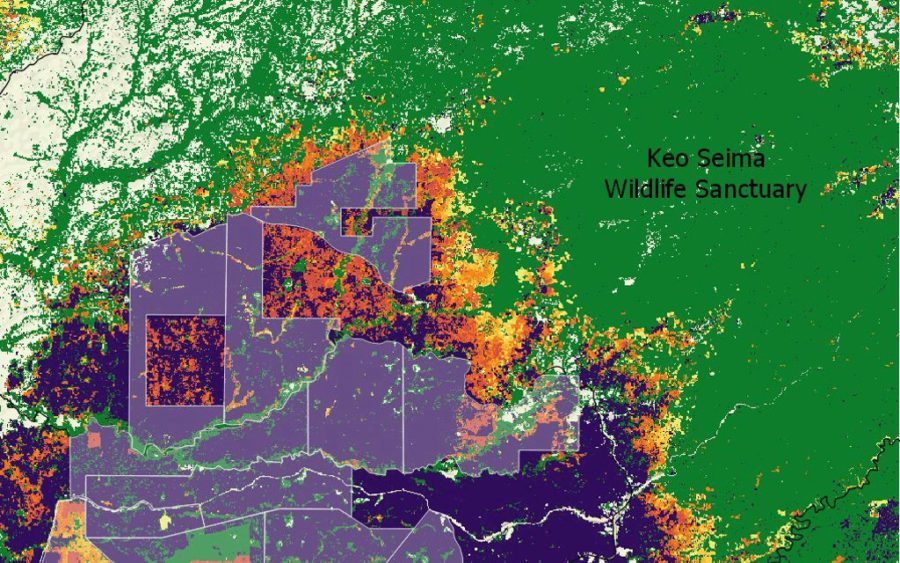

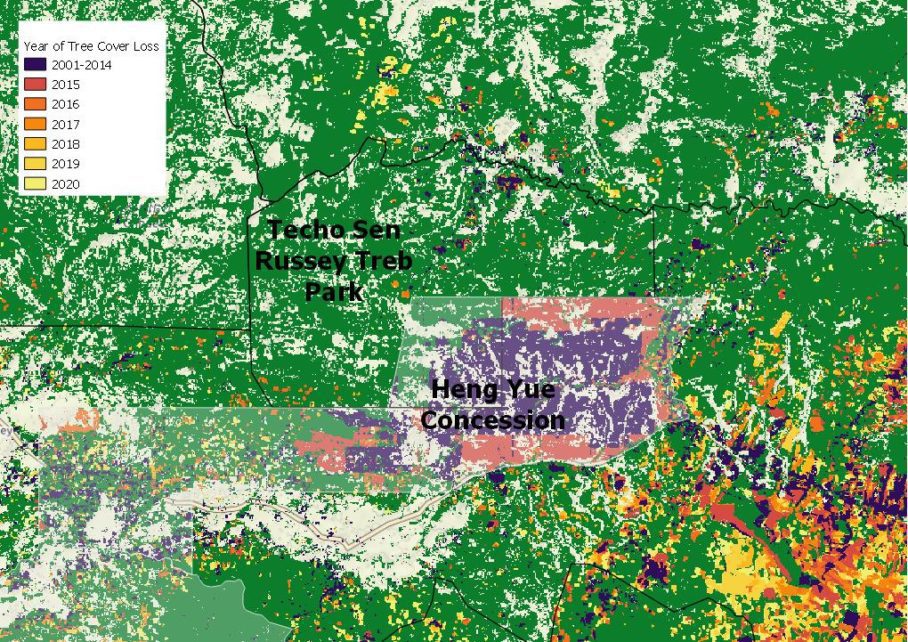

Using data from Global Forest Watch, VOD looked at how much of the tree loss recorded by the satellite imagery fell within protected areas, while counting only the deforestation of thick forest with tree cover density greater than 30 percent. In every map in this story, the dark purple areas represent tree cover loss that occurred between 2001 and 2014, while the range of red to yellow colors represents tree loss from 2015 to 2020, respectively.

Environment Ministry spokesperson Neth Pheaktra said the ministry “has no need to respond to a third party’s report,” and did not answer questions about what trends in deforestation the ministry witnessed last year.

Instead, he said the ministry has deployed 1,200 rangers across protected areas and strengthened law enforcement with help from local communities and NGOs.

Last month, a team from advocacy group the Cambodian Youth Network patrolled 55 km of forest in Prey Preah Roka Wildlife Sanctuary and found more than 100 cases of deforestation over a three-day period, said Heng Kimhong, head of research and advocacy for the organization.

The Global Forest Watch data indicates that Prey Preah Roka lost 612 hectares of tree cover last year, a 20 percent increase compared to forest loss in 2019.

Kimhong said that although the network is registered by the Interior Ministry, the Environment Ministry consistently rejects its attempts to share information about forest loss by saying the NGO has not registered a memorandum of understanding with the ministry.

He said he did not know if the Environment Ministry was investigating deforestation, but “I know only the Environment Ministry always rejected us and other organizations when we released some research or investigation research about increased deforestation in protected areas.” He added that activists had been banned or arrested for trying to provide evidence of illegal activity.

Richard Pearshouse, Amnesty International’s head of environment and crisis, said the Environment Ministry was “misusing” the Law on NGOs to stop community groups, indigenous people and forest defenders from patrolling the forests. But ignoring the satellite imagery would be “futile,” he said.

“The data will keep on coming and if the authorities want to avoid more bad news in future years, they should get serious about combating illegal logging in protected areas,” Pearshouse said.

He added that the rampant deforestation in Cambodia’s protected areas has an outsize impact on indigenous communities, particularly in Prey Lang, Prey Preah Roka in Preah Vihear and the Cardamom mountains. He said these communities rely on the forests and have proven to be “effective guardians” in their areas. The Environment Ministry banning unregistered community patrols has instead been beneficial to concessionaires operating in and around protected areas and “big interests” that benefit from illegal logging, he said.

“The Ministry of Environment has done next to nothing to prevent illegal logging but has banned the community environmental groups who protected the forest,” he said in a statement. “The Ministry is giving carte blanche to major illegal logging operations to run riot in Cambodia protected forests.”

Prey Lang

Across the board, Prey Lang Wildlife Sanctuary experienced some of the worst levels of logging. The protected area lost 9,119 hectares of tree cover in 2020 alone, increasing 21.1 percent from the loss in 2019. Prey Lang also had the highest average number of hectares lost annually between 2016 and 2020, at 7,348 hectares.

That average annual loss was almost triple what it was between 2011 and 2015, according to VOD’s calculations from Global Forest Watch Data. Prey Lang’s forest loss was under 1,000 hectares annually in the 2000s, then hovered between 1,000 and 4,500 hectares of annual loss in the first half of the 2010s.

In 2016, Prey Lang lost 10,536 hectares of forest from its dense forest cover, the highest annual deforestation seen to date. In May of that same year, Prey Lang was decreed a wildlife sanctuary.

Matthew Edwardsen, chief of party of USAID’s $21-million conservation program Greening Prey Lang, agreed that deforestation was rising in Prey Lang Wildlife Sanctuary due to demand for wood locally and internationally, as well as illegal timber laundering. He said the illegal activity was due to “many factors including weak law enforcement capacity and lack of accountability on the ground,” saying the project raised its concerns about logging to the government.

When asked what could have been done better by USAID’s program to protect Prey Lang’s remaining forest, Edwardsen responded that the all levels of the Cambodian government should prioritize conservation in the sanctuary, and called for “continued coordination among all stakeholders” on environmental protection.

Late last month, the Global Initiative on Transnational Organized Crime named multiple concession-holding companies as culpable for cutting luxury timber, hacking residents’ resin trees and exporting logs illegally from Prey Lang Wildlife Sanctuary and, to a lesser extent, Prey Preah Roka. The report connected forest activists’ on-the-ground accounts with satellite data and customs documents to show that a series of agro-industrial land concessions — PNT, Thy Nga and Sam Oeun Sovann on the west side of the sanctuary, and Think Biotech to the east — appear to be sawing timber on site and shipping wood through the Angkor Plywood factory and into Vietnam, in violation of Cambodia’s timber export bans.

Keo Seima

Mondulkiri province’s Keo Seima Wildlife Sanctuary lost 3,639 hectares last year, almost double the forest loss seen in 2018, according to the satellite data. However the average forest loss over a five year period fell in Keo Seima, from 6,375 hectares annually between 2011 and 2015 to 3,564 hectares lost annually between 2016 and last year.

The Global Forest Watch data show continued deforestation around a cluster of rubber concessions in the southern part of the sanctuary, which has been cleared by subsidiaries of Vietnam Rubber Group for years. But the imagery also indicates increased patches of logging on the plantation’s eastern side, within O’Reang district and near the adjacent Wuzhishan concession, a pine plantation, as well as a proposed airport.

Simon Mahood, senior technical adviser of WCS Cambodia, the conservation group that oversees Keo Seima, described Global Forest Watch data as “notoriously inaccurate in quantifying change in deciduous and semi-evergreen forest” — the types of trees present in the sanctuary.

However, he said that deforestation was rising in some locations, largely due to land speculation and people moving into the province, especially as infrastructure like roads was developed. His description of locations with increased deforestation — the southern part of Keo Seima and the area near the proposed airport — aligned with new spots of tree cover loss that appeared in the data.

“Plans to develop Mondulkiri province through, for example, the proposed airport, have led to land speculation in forested areas close to Sen Monorom,” he said, adding that to the south, “opportunistic clearance of forest has continued where the protected area abuts agricultural concessions.”

Keo Seima is also the site of a REDD+ program, earning its first $2.6 million in carbon purchases from Disney Corporation in 2016.

Other Areas

Global Forest Watch data indicates that much of the recent deforestation in protected areas are overlapping or next to economic land concessions. In Kulen Promtep Wildlife Sanctuary, earlier deforestation between 2001 and 2015 occurred around clusters of Cambodian, Thai, Vietnamese and Korean concessions, mostly in Oddar Meanchey province. But in 2017 through last year, much of the new clearing appeared within and near the Metrei Pheap Kase-Ousahakam agro-industrial company, which has been wrapped up in a land dispute with Preah Vihear residents.

Satellite analysis of Boeng Per Wildlife Sanctuary shows that the most of the concessions granted within the sanctuary were cleared before 2015, but in recent years the clearing spread out from the concessions and into the remaining forest cover.

The lost tree cover at some protected areas is smaller than that of large sanctuaries like Prey Lang and Kulen Promtep, but deforestation has plagued sanctuaries of all sizes.

Ream National Park had only a modest 13,600 hectares of forest cover in 2000, but the park hemorrhaged tree cover as development of two tourism concessions kicked up, losing 13 percent of its remaining forest cover in 2018 and another 16 percent in 2019, according to calculations by VOD.

The Techo Sen Russey Treb park in Preah Vihear province is relatively small, with just under 9,000 hectares of tree cover in 2000, according to satellite data, but the sanctuary last year experienced a sharp increase in deforestation for its small size — from 3 hectares of loss in 2019 to 21 hectares in 2020.

Despite the relatively small size, Royal Academy of Cambodia president Sok Touch said the academy, which oversees the Techo Sen Russey Treb forest area for protection and research projects, has faced challenges to stop cutting in the forest.

The academy has tried to teach residents how to collect non-timber forest products like bamboo, mushrooms and resin, as well as raise cows. But Touch says that clearing land for development and logging luxury wood is rampant.

“Our education campaign has lasted about a year but [we] haven’t gained anything,” he said.

Newly planted trees have been burned by people, and patrollers in the sanctuary have started confiscating equipment to stop loggers. Touch said nearby residents were logging the protected area. But much of the clearing in Techo Sen Russey Treb falls within the Heng Yue concession, one of five landholding Chinese sugar companies accused of clearing forests and causing indebtedness among nearby residents.

“How can we conserve the forest when they do like this. … It is like in a Hollywood movie and they tried to hack at us,” Touch said.

Additional reporting by Mech Dara