Ho Sambath, 53, claims no one wanted land on Koh Meas when he first landed on the river island in the early 1980s. He says he’s the one who cleared the land and started selling off pieces of it. When fishers and farmers were kicked off Phnom Penh’s Koh Pich, or Diamond Island, in the early 2000s, he offered them affordable land to resume their farming.

Though Sambath does not know what development is coming, he knows someone powerful has taken interest in his island. Around 2017, local authorities stopped signing papers approving “soft” land sales — more informal sales signed by commune or village officials — and he noticed people filling sand on riverbanks close to his village. The man says he’s now concerned that the government is going to offer him less compensation than he could sell the land for.

“We know this land will be bought, but the worrying thing is the price [they will offer],” Sambath says. “We’ll see whether they come to do honest business or they come to take it.”

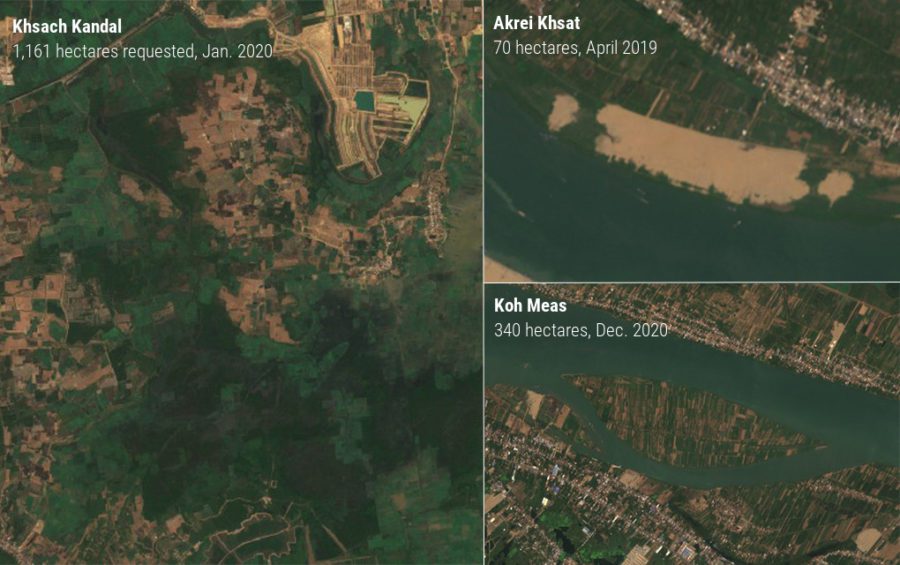

Some 340 hectares of the island that Sambath cleared was granted in December to Khun Sea, a property developer who has developments across Kandal province on land received from the government, which has continued a flurry of state-land privatizations.

Cambodia has in recent months privatized more than 120,000 hectares of land, lake and sea, according to a VOD review of government documents published so far this year. The vast majority of it was newly privatized land within Koh Kong protected areas, but individuals and businesses also received new grants of Phnom Penh’s Boeng Tamok lake, Preah Sihanouk’s Prey Nob district and Kampot seafront.

If they grow lemongrass and bananas, how much can they earn from it? We turn it into an economic, tourism and commerce city and make our country developed.

After privatizing Koh Meas for Sea, the government issued three 20-hectare pieces of Tamok lake and shoreline in December: one to the Health Ministry, another to Lun Hak and Chhun Chanthy, and a third to 16 military families.

The government has also granted areas of the Cambodian sea to individuals. In Kampot province, the government gave 120 hectares of coastal waters to the provincial department of tourism and another 80 to IGB Cambodia, a company that plans to develop an artificial beach, according to the news website Construction & Property. IGB’s chair Chea Sok Heng also leads Petronas (Cambodia), a subsidiary of the Malaysian oil and gas giant that once had gas stations in the country.

Canopy Sands Development, a project within Prince Holding Group, received 100 hectares in March, which the company will convert to a cluster of six islands off the coast of its massive sandfilling project. The map printed in the sub-decree shows six islands of varying sizes off the point of the Prey Nob peninsula, saying it received the land in exchange for cleaning polluted waters.

The government also allocated more than 46 hectares in Preah Sihanouk’s Stung Hav district to Chhek Sokha and Chea Srey Touch. Sokha could not be identified, but a person named Chea Srey Touch is listed as chair of the Phnom Penh-based company Hai Sun (Cambodia) Investment Import Export.

The government further privatized nearly 127,000 hectares of protected areas throughout Koh Kong province, divvied up into eight sections ranging from 6,280.26 hectares to more than 30,000 hectares, though it did not specify the purpose or ownership of these plots.

Not all of the land plots found in this year’s sub-decrees were grants to companies or individuals: In January, two mountains in Kampot province were designated for tourism and protection uses, while Pring lake in Prey Veng province was set aside in February for “sustainable development,” according to the documents.

Khun Sea’s Kandal Landscape

When the paved road from the sparse 7NG development ends in Khsach Kandal district, a dirt road continues into a small community of about a dozen families living in shack houses overlooking tangles of grasses and shallow ponds. There are no developments out here, a group of women tell reporters, only lotus.

A power line runs alongside their road, but the residents say the lines aren’t live — the community uses batteries and solar panels for power.

For their food and a bit of income, a 36-year-old resident who gave her name as Thary says they rely on lakes to the north of their community for fishing.

In this area, Sea requested a permanent lease on 1,161 hectares of land and lake in January 17, 2020. The government on the same day privatized 886 hectares within that plot — without specifying the recipient, according to the two sub-decrees. The residents had never heard of the developer, nor the change in their land’s status; they were only familiar with the longstanding 7NG development that borders their stretch of road.

Sea could not be reached through emails and phone numbers listed under his business on the Commerce Ministry, and his listed office could not be found.

Thary says the residents rent farmland for about 300,000 riel ($75) per year per hectare, but she says the real landowners are wealthy people in Phnom Penh, though she doesn’t know their identities.

She’s slowly started to sell off the land that she bought about 18 years ago with a soft title, so far getting around $3,000 from brokers. Her land was originally 30 meters long but she had cut it down to 6 meters in length, with only a small piece of land for her home.

“They buy it and just fill it up,” she says. “Our homes are getting smaller and smaller.”

Though Sea’s plans for the lake are unknown, the tycoon has been known for creating land from water. He is also behind a 70-hectare Mekong river infilling project about 10 km away in Kandal’s Akrei Khsat commune, for a “satellite city” with shopping malls, condominiums and a resort. Farmers and fishers who worked near the new Phnom Penh airport development in Kandal’s Kandal Stung district earlier this year also claimed that Sea was holding onto pieces of that wetland.

Thary says fishing with net traps in the lakes of Prea, Knong and Veal Samnab was their main source of income, but that has become harder due to low water levels and poor prices at the markets.

Koeth Ky, 61, another resident, says she is borrowing money from others in the community, saying she can only fish on the days it rains.

“Life is very difficult. In one day, we can only earn enough to live for one day,” she says. “Now I need to buy rice day by day.”

Evicted Again?

“Wherever you dropped a vegetable, it would grow,” recalls Yi Tuol, 50, saying she was very happy in her previous home.

Tuol is nostalgic for Phnom Penh’s Koh Pich, from where she was forced to leave in the early 2000s. She is not as happy at her current home on Koh Meas, which the land tycoon Sea was just granted in December.

Tuol and her extended family once lived near what’s now the middle bridge of Koh Pich, which she says has become unrecognizable.

On Koh Pich, she used to grow a wider range of vegetables and quickly swim across the canal to sell vegetables at Doeum Kor market, whereas now she must wake up at 3 a.m. to take her papaya, the main fruit she can grow on Koh Meas, to market. The water from the canal separating Koh Pich and mainland Phnom Penh used to be a bit of a sewage dump, so it made for great fertilizer, Tuol remembers.

Though it’s less convenient, she still doesn’t want to leave her new home that she’s inhabited for about 15 years, nor receive low compensation — rumored to be $20 per square meter.

“People don’t want to sell [land] at that price. Can you buy a house for the same price? We’re starting to get nervous,” she says.

From her experience in Koh Pich, Tuol’s sister, Yi Ti, sees that authorities push residents to evacuate land for inadequate compensation: They first encourage and persuade them to take the money, and then they use force.

The community bought a boat that they can share when they started getting concerned about land sales on Koh Meas. Ti recalls that when they were being evicted from Koh Pich, the ferry driver stopped taking them across the river to mainland Phnom Penh in order to pressure them from going, so they keep the boat to make sure that won’t prevent them from selling their crops in the future.

“We just want to know what’s going on. We’ve only heard speculation for the past four or five years,” she says. Ti and her sister say they won’t be willing to leave this land easily.

“Some rich people buy the land but they do nothing with it,” she says. “At least we use it.”

According to a 2011 Commerce Ministry document archived by Open Development Cambodia, National Police deputy commissioner Yim Leang is a shareholder in Khun Sea Import Export. Leang’s father is Deputy Prime Minister Yim Chhay Ly, who is also chair of the governmental Council for Agriculture and Rural Development. Leang is married to Chea Sophamaden, the daughter of Land Management Minister Chea Sophara.

Mao Phirun, a Kandal provincial councilor and former governor, says it should take some time before the government turns to evicting residents of Koh Meas, as they need to appropriately relocate the residents.

“They have two rights: to cultivate and to use the land. But [they] have no right to manage the land because it does not belong to them and it belongs to the state,” he says.

However, he says these developments are worth the loss of farmland, pointing to the economic promise of Koh Norea, the Overseas Cambodia Investment Corporation’s second satellite island development after Koh Pich.

“If they grow lemongrass and bananas, how much can they earn from it? We turn it into an economic, tourism and commerce city and make our country developed,” he says, adding that if people wish to preserve small patches of forest, “they are falling and dying on the piles of gold and diamonds.”