In the “smart cities” of the future, Cambodian urban spaces would be designed around digital infrastructure. Our cities might, for instance, analyze and optimize the flow of digitally tagged cargo. Traffic control systems, which use artificial intelligence, may shepherd flows of driverless vehicles through thoroughfares lined with sensor-equipped traffic lights.

These futuristic so-called smart solutions may seem like they’re years away from becoming a reality, but some versions of these systems are already being actively explored and implemented.

Siem Reap city authorities, for instance, have installed a city wide CCTV network focused on data collection and analysis to monitor traffic and ensure public safety with assistance from the Japanese development agency. Six more smart city projects are planned for Siem Reap alone.

Phnom Penh is also steadily expanding its own CCTV network, while also implementing a logistic management system in the planned Phnom Penh logistics complex. This system utilizes digital track-and-trace solutions to achieve better inventory visibility within a supply chain.

And authorities in Battambang have plans to use technological solutions to manage waste disposal. Provincial governor Sok Lou has said he envisions a system where garbage bins and trucks will be tracked and monitored using chips. He also added that parking is an area that could use a smart solution.

These examples and many other digital solutions, are part of a larger effort by the “Asean Smart City Network,” a platform of 26 cities in the region, collaborating toward the common goal of smart and sustainable urban development. Phnom Penh, Siem Reap and Battambang are all members of this network of cities.

Yet Cambodian city planners would benefit from some degree of caution in just how much they prioritize these tech-focused solutions. Our planners and policy-makers must not let the adoption of digital technologies overshadow simpler, cheaper and more sound urban policies that can offer practical and scalable solutions.

What Is the Asean Smart City Network’s Purpose?

The objective of the ASCN is to ensure that cities achieve three strategic outcomes: high quality of life, competitive economy and sustainable environment, and it does so mainly by leveraging digital technologies.

According to the “Asean Smart City Planning Guidebook,” published in 2022, “Smart cities in Asean aim to address such issues and challenges and provide new value to the citizens, by leveraging digital infrastructure and data as an enabler.”

Interestingly, one of the key principles in the guidebook is “Focusing on the vision; aim not only to implement new technology, but focus on solutions which resolve the issues.”

However, this point is not reinforced nor emphasized anywhere else in the guidebook. Just as when your only tool is a hammer, everything starts to look like a nail, the majority of priority actions exemplified under the guidebook only focus on technology-based solutions.

For example, in the civic focus area, the introduction of digital payment solutions is identified as a priority action. Similarly, in the mobility and urban resilience focus area, digital management systems for traffic and flooding are prioritized. And the majority of suggested actions mainly focus on technology as an enabler.

Since the ASCN is a non-binding guide, it cannot enforce solutions, nor provide concrete details and regulations to ensure consistent implementation. This leaves a lot of room for individual countries and cities to pick and choose which solution to adopt and how to implement them, decreasing effectiveness and making a shared integrated solution impossible.

Moreover, this deliberate vagueness in combination with a heavy emphasis on digital infrastructure and technology have the potential to unintentionally lead Cambodian policy makers to become over-reliant on smart technologies and to overlook effective urban policies.

The positive impacts of digital technology in monitoring, analyzing and managing cities is undeniable. But smart technology implementation must be built upon the firm footing of sound urban planning policies.

Cambodia First Needs Smart and Sound Urban Policy

Before implementing smart city solutions, Cambodian urban planners must first adopt urbanization policies which prioritize people, environmental sustainability and inclusive economic opportunities. Let’s examine some policies which can do just that, at a fraction of the time, cost and complexity compared with digitally-enabled solutions.

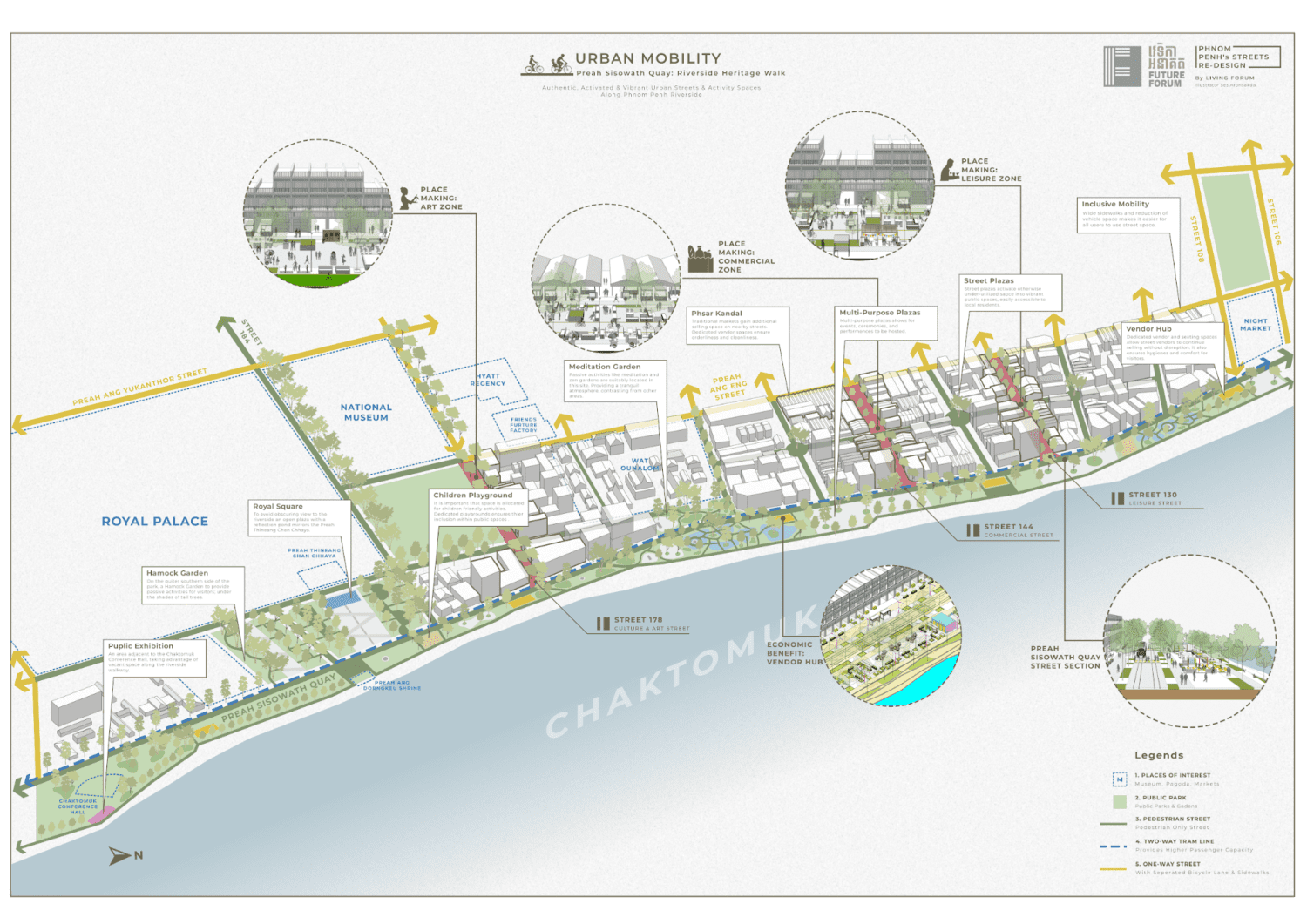

First, Cambodian cities should adopt a compact city approach to urbanization. This means implementing policies which incentivize developers to construct homes, schools, shops and workplaces in comfortable, human-scaled spaces located in mixed-use and optimally dense city blocks. Ideally these spaces would be well-connected by foot and cycling paths, served by excellent public transit connections.

Several policies in particular should be prioritized to help Cambodia’s cities develop in this way. Most crucial are land-use concepts like “Transit Oriented Development,” which encourages the development of optimally dense mixed-use neighborhoods within walking distance of public transit stations.

Urban planners can assess users’ “mobility profiles” to tailor a building’s placement to fit with the local street network and allows planners to account for how users commute to and from different types of buildings, and to gauge the intensity of traffic generated by users of that space.

Walkable mixed-use neighborhoods still require an effective transit system for long distance travel. This remains a challenge for Cambodian cities as poor walkability, a disjointed network, and poor reliability plagues the capital’s public transit system.

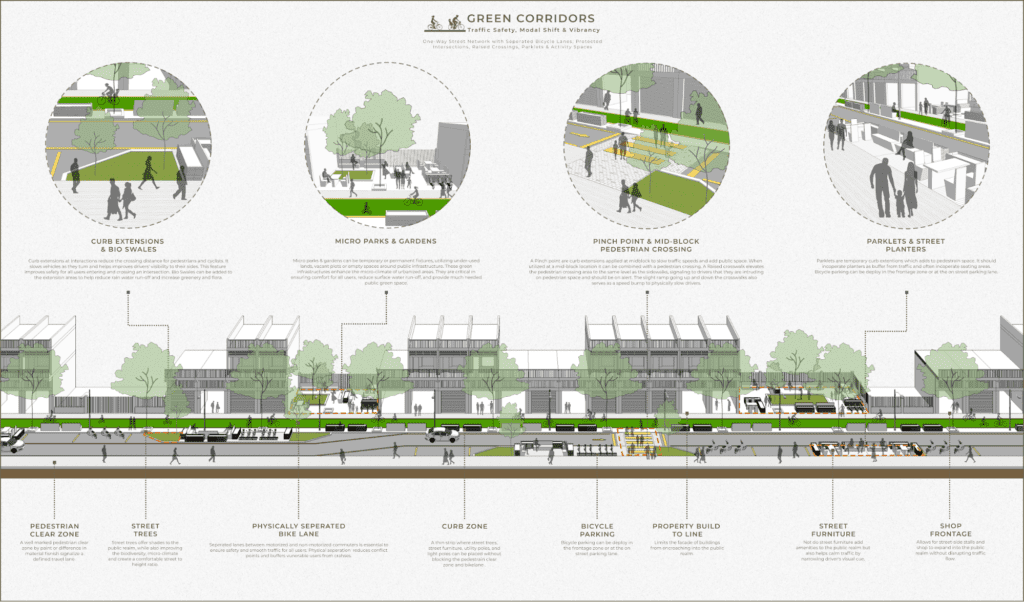

A possible solution is to disentangle public transportation and active commuters from private vehicle traffic. This strategy would entail carving out public transit priority lanes and designated lanes for pedestrians and cyclists. Disentangling urban traffic not only increases efficiency, but also boosts safety, as each mode of commute is not forced to compete with the other.

The disentanglement of Cambodia’s urban streets would be even more successful when paired with policies which actively combat traffic congestion. Parking policies should also be revised to replace our current parking minimum with a parking maximum requirement. A policy based on parking maximums would reduce the number of parking spots available, and significantly reduce trips by motor vehicles.

Other approaches could be designating car-free zones within the city center — like the city of Ljubljana which is car-free in its historical city center — or to levy a congestion charge on vehicles which enter the city center, further dissuading private vehicles usage and mitigating traffic congestion.

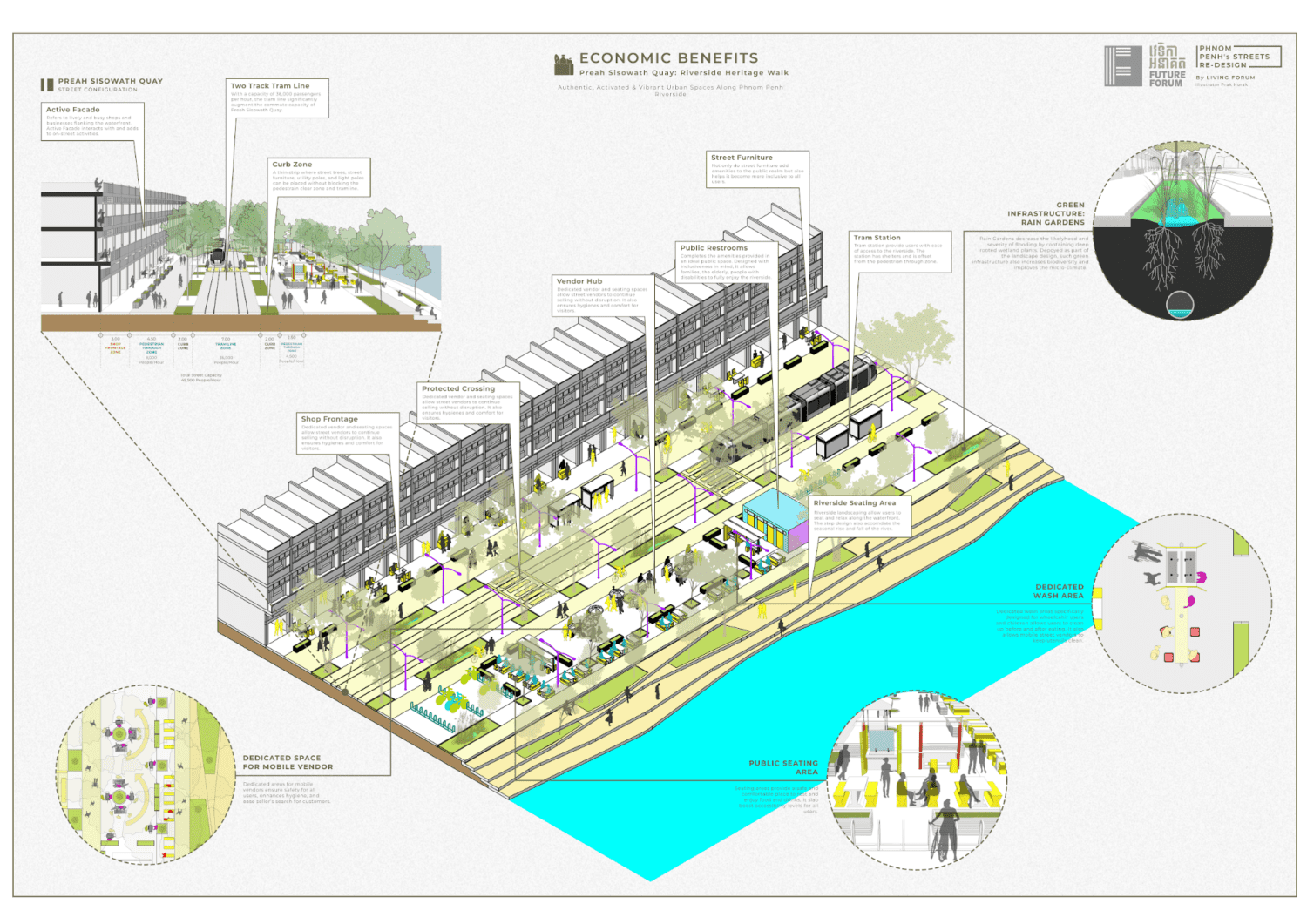

To achieve a holistic approach, Cambodia should also consider reforms to street design, in favor of an active street design philosophy. Actively designed streets prevent motorists from undertaking dangerous maneuvers by narrowing driving lanes, utilizing chicane patterns for vehicle lanes, placing curb extensions, raised crosswalks, and other physical interventions. Such efforts also allocate more space for public transit and active commuters, while improving road safety for all.

This dovetails with efforts to reduce space for private vehicle traffic, and to pedestrianized streets and give back space to citizens. Interventions like adding parklets to increase public spaces, provide public amenities like seating, vendor space, public art displays and playgrounds.

Former vehicle space could be converted into bioswales — a combination of storm water drains and gardens — to improve our cities’ microclimates, to help capture flood water, and to reduce urban heat islands to the benefit of all citizens. By repurposing space for people, the urban landscape becomes more inclusive, safer, less polluting, more pleasant and welcoming, helping to build an inclusive economy and cohesive society.

This is not an exhaustive list of practical urban policy solutions suitable for Cambodian cities, there are many more interventions that are appropriate. Compared with digitally enabled solutions, these interventions offer less complexity and less cost, while also tackling the root causes of the issues they are meant to address. Moreover, these policy and design changes can be achieved without relying on outside assistance and funding.

Urban Policy First

Cambodia must avoid falling for the notion that smart technology is the answer to everything. After all, cities are complicated, interconnected machineries which require well-balanced stewardship. Getting tunnel visioned into implementing only digital technology-enabled solutions is blinding us to practical and scalable policy solutions which address many fundamental problems.

Cambodia must first focus on sound policies before it can turn to smart technologies. In the future, Cambodian cities can be — and should eventually be — buzzing with technological marvels. But before we can get there, Cambodia first needs to enact simple, scalable, human-centric urban policies.

Ses Aronsakda is a junior researcher at Future Forum. Educated as an architect, he conducts research on Phnom Penh’s urban planning with interests in all aspects of cities and urban design.