SIEM REAP — After a year in prison on an incitement conviction for his music, 22-year-old rapper Kea Sokun was released from a Siem Reap prison on Friday and returned home with no regrets about his songs or his refusal to apologize for the lyrics in court.

“Going back, I would not have said sorry,” he said through a translator from his childhood bedroom on Friday shortly after his release. “Because I believe that I did not do [incitement] like what they said.”

Following Sokun’s arrest in September of last year, the Ministry of Culture pressed charges against Sokun and a collaborator for incitement for his controversial, nationalist songs which included lyrics like “stand up,” “I’m opposed to the dictator,” and “the other race is encroaching.” The courts convicted him to a one-year jail sentence in December.

Arriving from the Siem Reap prison by tuk-tuk, Sokun received Buddhist blessings from his family outside their home just down the road from Angkor Wat.

Sokun walked over three fires in a ceremonial cleansing before kneeling as his mother and father poured water strewn with flowers over their son’s head to welcome him back.

“I just want to spend time with my family first,” Sokun said. “I will rest for a while but I still want to keep making music. Because music is art which can reflect society.”

Though Sokun has received more attention than most for his case, he’s one of more than 150 to be charged with incitement since last year, alongside activists, opposition politicians and ordinary citizens posting satire or alleged misinformation on Facebook. The Information Ministry said it identified 1,061 “fake news” items this year as of August.

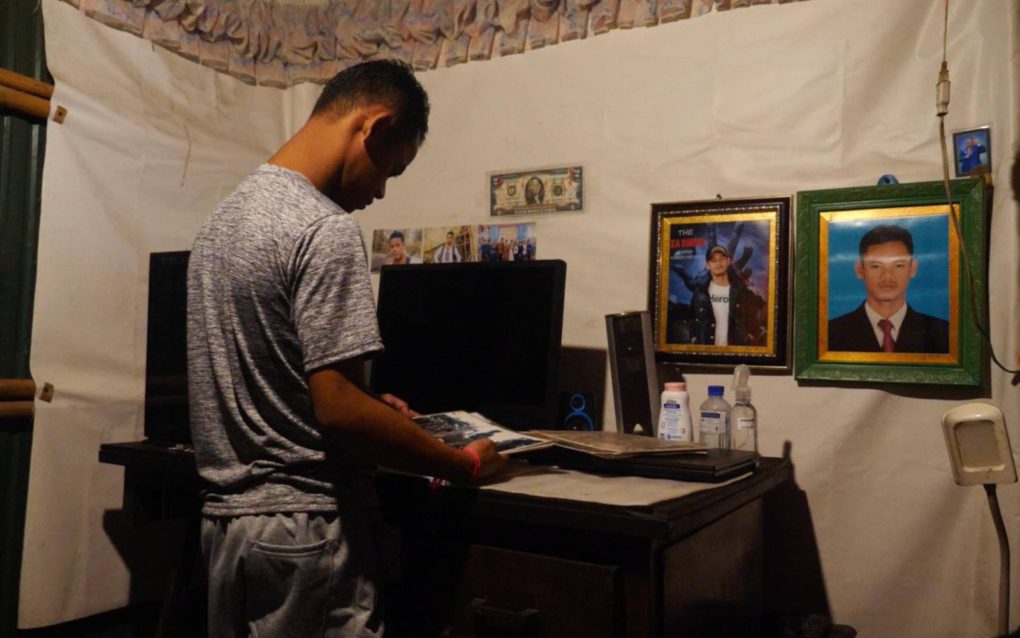

Eating chicken soup from one of their own hens, the family said they had missed their son most during meal times. In the year of waiting, each had found their own ways to mourn his absence.

His mother listened to his songs from her phone while she knit elaborate tapestries for him.

His father took to regularly polishing Sokun’s laptop, the one the rapper saved up to buy from his job and which exposed him to social issues.

And Sokun’s sister thought about him every week when she cooked his favorite meals of fried fish to deliver to the prison, until Covid-19 outbreaks halted in-person visitation.

While Sokun served his full sentence, there had always been another option available. Apologize publicly, like his collaborator, a minor who was released after the trial.

Sokun’s conviction and prison sentence were upheld during an appeal in Battambang in June, with the judges reviewing his lyrics again and forcing Sokun to acknowledge that the lyrics had a negative effect on the government. In his initial appearance at the Siem Reap Provincial Court, Sokun had remained fully defiant.

“Sokun raised his hand up to the judge and said ‘Please find justice for me,’” said Sar Vannara, the Siem Reap Licadho coordinator who witnessed Sokun’s first trial. “There might be some people laughing at Sokun’s decision. But in my opinion, Sokun knew that he wasn’t wrong, that’s why he asked [the judges] to find justice.”

Others convicted of incitement still linger in prison, including a woman who was recorded throwing a shoe at a billboard of Hun Sen.

Yet incarceration has increased Sokun’s message and popularized his platform further. He currently has more than 227,000 subscribers on Youtube, and the several songs scrutinized by the government have found new life online, gaining millions of views.

While some of Sokun’s initial YouTube videos stuck to more conventional rap content like diss-tracks and love songs, in the last few years his music took on a distinctive edge, often on the topic of economic inequity.

“The rich are worry-less, already living in happiness,” he rapped in one song, “Sad Nation.” “The poor like us are constantly vulnerable.”

Sokun dropped out of school in the 9th grade to work in photography to earn money for his family. They live on titleless land in the forests beside the Angkor Wat, imbuing Sokun with a strong sense of Cambodian pride, his family said.

Sokun’s music has pulled from nationalist tropes and anti-Vietnamese stereotypes, particularly in the song “Khmer Land,” which went viral on TikTok and prompted his arrest, says Siem-Reap based researcher Tim Frewer, who studies Khmer nationalism.

“He doesn’t even need to say it explicitly, doesn’t even say it anywhere in the song,” Frewer said. “But it’s quite clear from the context — suggesting that the people in power are being tricked, that there’s someone behind pulling the strings — falling back on that idea that there’s still this influence and legacy of the Vietnamese.”

Sokun’s lyrics in “Khmer Land” drew on rhetoric similar to activists like incarcerated unionist Rong Chhun who have often framed their social commentary and criticism of Cambodian society through Khmer nationalism drawing on anti-Vietnamese stereotypes, according to Frewer.

Sokun and his family denied anti-Vietnamese sentiment or any kind of political messages to his music, saying his songs were meant only to reflect the “reality” of society and foster civic unity.

“In [the song] Khmer Land, I wanted to talk about the ancient times,” Sokun said. “And it is about how every citizen should wake up to love their society, religion and nation.”

Whether or not Sokun will continue to produce music and take on social issues and politically charged topics in his rap remains to be seen. His family would like him to take a break, but they say they will stand behind him whatever he decides. Sokun still has a six-month suspended sentence, which could send him back to prison in the event of a misstep.

“For me, no matter what decision my brother makes I will support him, stay by his side and motivate him,” said Kea Channa, his sister. “But I am still afraid for Sokun’s safety.”

“I don’t know if he will be arrested again,” said his mother, Boun Nai. “But if he wants to do it [rap], he’ll do it. I trust my son.”