Timber, monkeys, orchids, sand: Cambodia’s protected areas and natural resources continue to be a lucrative source of income, in spite of all the promises (and international funding) to protect them. Above all else, the hunger for land has consumed Cambodians and foreigners alike, triggering a constant race to cut down forests and fill in lakes. But this insatiable craving has uprooted several communities in 2022, not to mention the ecosystems destroyed in its path. And often after the land is cleared, it sits empty.

Patrollers consistently find evidence of organized — sometimes industrialized — logging in Prey Lang Wildlife Sanctuary, Prey Preah Roka Wildlife Sanctuary, Mondulkiri protected areas and the Cardamom mountains and Phnom Oral landscape.

Indigenous communities have experienced heavy pressure to give up their land: Kuy activists protested the loss of Boeng Per Wildlife Sanctuary land to the company Sambath Platinum, while Suoy residents in Kampong Speu tried to stop encroachment of a company connected to Hun Sen’s nephew. Indigenous groups from Ratanakiri, Mondulkiri and Preah Vihear also faced court questioning and pressure after protesting against different companies.

Authorities also bullied ethnic Vietnamese communities in Cambodia, relocating them from the riversides of Phnom Penh and floating villages in the Tonle Sap. Those that were forced to move to land in Kampong Chhnang saw their new grounded homes underwater as the lake swelled.

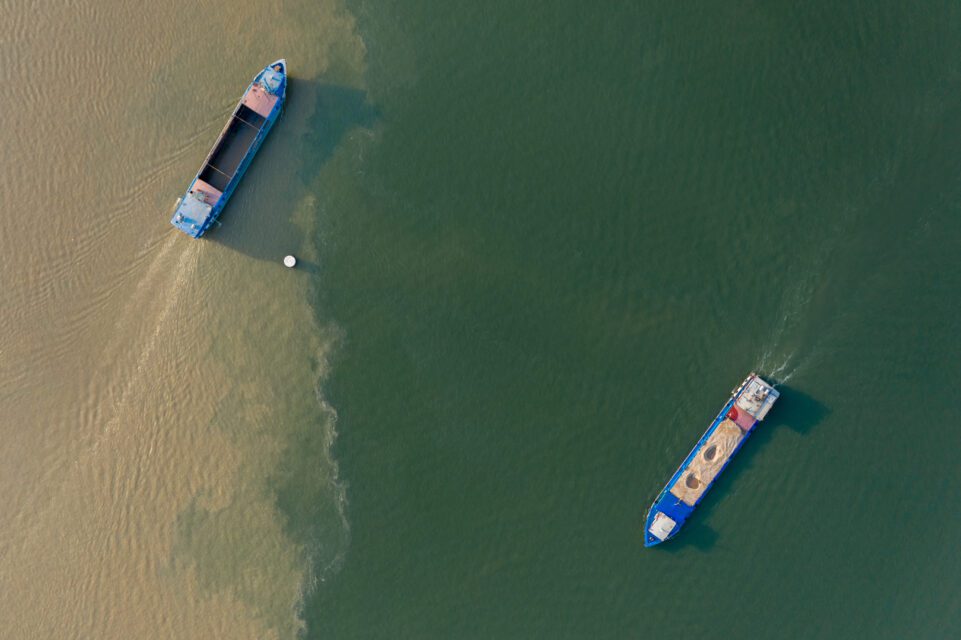

Pollution and litter were at the front of Cambodians’ environmental concerns, starting the year with a campaign to clean canals as trash seeped into election politics. Clutter was even used as an excuse to relocate residents from a canal. Sand mining vessels are traversing the trash in Phnom Penh’s rivers to extract the low-cost, high-value construction resource, and reporters witnessed sand barges from Cambodia crossing into Vietnam.

Ten years have passed since renowned forest activist Chut Wutty was killed under suspicious circumstances in the Cardamoms, but rather than celebrating activists, an outspoken indigenous land defender was jailed.

The year ended with a shock for the Agriculture Ministry, which has been working hard to maintain its image. The U.S. government opened a lawsuit against two Agriculture Ministry officials for trafficking wild macaques through a breeding facility, with U.S. officials arresting Kry Masphal on his way to an international biodiversity conference. When reporters found out, they traveled to Pursat to meet workers at Vanny Bio Research and monkey hunters in Veal Veng district, whose accounts align with the U.S. lawsuit. A U.S. lab monkey importer said it would stop buying macaques from Cambodia as a result, but Prey Lang forest activists still found signs of monkey hunters in the protected area after pressure from the U.S.

Forest Crusader’s Death Couldn’t Stop Destruction in Cardamoms

Environmentalist Chut Wutty was killed 10 years ago today, shot dead by a soldier in the Cardamom forest. The forest was being cleared by a company with high-level connections, including to the military. The area now contains large patches of cleared forest and a cascade of hydropower dams.

Major Land Disputes

The government has continued redistributing state land to elites in its regularly-issued sub-decrees — often as a form of compensation to tycoons and companies, or seemingly sold at deep discount. This year’s prominent recipients include an Orkide director, a singer who calls himself “legendary,” the progeny of an infamous tycoon, a four-star general, Hun Sen’s sister, Hun Sen’s assistant, and a casino and scam tycoon.

One Land Ministry official encouraged the filling of Boeng Tamok lake, but residents at Boeng Tamok lake have grown increasingly frustrated as the lake is parceled away to powerful tycoons and government officials’ family members. This year they protested and cursed officials who took their lakeside homes, only to end up questioned in court.

This cursing ceremony is for those who steal the people’s land [to suffer] in any way — drowning in a boat in the middle of the river. A plane crash. A car accident. Until they are all dead. If one of them is still alive, please go crazy.

— Boeng Tamok resident Sa Dava

The hunger for new land turned toward natural features in other provinces: Boeng Trea lake in Kandal and the resort site Tonle Bati in Takeo.

Metta Forest, within the Phnom Oral Wildlife Sanctuary, was a tranquil location where a monk lived in harmony with nature, until excavators tore it apart to create land for military families, but residents say the destruction went far beyond the boundaries they were supposed to clear. Prom Thomacheat, a monk who made a life in Metta forest, lost his hut to the clearing.

The Apsara Authority began mass evictions across Angkor Archaeological Park in Siem Reap after Unesco commented that the park should be beautified, pushing residents who made their livelihoods on Angkor Wat tourism to Run Ta Ek, a remote area 25 km away from the temple where Prime Minister Hun Sen promised a future satellite city but residents struggle to find jobs. Almost 10,000 residents accepted the relocation; others say they haven’t received compensation or land titles; some have been protesting the relocation, including a village chief who was fired for joining in; and neighboring residents feared they would lose their homes and jobs amid the confusion.

One land redistribution really riled the public, when tycoons Khun Sea and Leng Navatra were granted huge tracts of Phnom Tamao forest in Takeo province. Construction teams rapidly cleared more than 500 hectares of trees until Hun Sen called off the clearing and ordered trees to be replanted. After the highly photographed replanting campaign, reporters returned to Phnom Tamao to find hundreds of Hun Sen’s bodyguards who confiscated phones and equipment and detained reporters for six hours. The premier later said the unit was called to flatten the land and fill sand, and the bodyguards left a fly-covered park in the cleared forest.

The government also pursued a crackdown on flooded forest clearing, farming and fishing in the Tonle Sap lake and floodplain area, which seemed to be cleared of forest for years before the campaign. Authorities punished some provincial officials but let the ex-governor go without corruption charges. Farmers were later allowed to tend crops on more than 6,000 hectares of the floodplain, but fishers faced intense — and sometimes politically-tinged — crackdowns.